For a subject that may seem unimportant, clothing was a serious business in Berkhamsted involving countless straw plaiters, bonnet makers, milliners, stay makers, seamstresses, dressmakers, right up to industries such the local “rag trade” at the Mantle Factory.[1] At a Holiday Fair in 1819, items of clothing were considered suitable prizes in sporting events: “A pair of breeches to be jingled for”, a linen shirt for men, a Holland Chemise for women, a pair of shoes in the sack race.[2]

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, clothes or the wherewithal to make clothes (materials, lace, ribbons) constituted 72 per cent of the goods stolen, most often from shops or houses and sentences were harsh for the perpetrators.[3] Not including the distinctive uniforms worn by firefighters, police, nurses, postmen and transport workers (provision of which would have been a boon for poorer members of the community) and with the help of criminal records, let’s investigate the clothes worn by local working people.

Farm workers

“The Anglo-Saxon tunic still exists in the smock-frock, a species of overall worn generally by the peasantry and some farmers in England.”[4] Reaching below the knees and made of course linen, smocks were ideal for outdoor work, favoured by farmers and labourers alike and affording protection in all weathers, some with a water-proof coating of linseed oil.[5] However, their voluminous design was dangerous when operating machinery as numerous reports of accidents with thrashing machines and cart wheels can attest.

The smock-frock was all but extinct by 1903, but it was still in evidence locally in the mid-nineteenth century. Residing at the Berkhamsted workhouse in 1851, twenty-year-old Joseph Grover was charged with stealing a smock-frock and two handkerchiefs.[6] The Deputy-Chairman was stern in his rebuke to Grover: “Your offence is aggravated by the circumstance that you were… provided with food and clothing, and that you robbed a poor man who was sleeping with you”. Groves was imprisoned for six months hard labour, with solitary confinement for a week in each month. It would be transportation for him if he re-offended.

It was early one summer morning in 1866 and, hearing a report of a gun, Samuel Dell set off to catch trespassers on Earl Brownlow’s land. He “took hold of one man whose head was disguised by a smock frock”.[7] In 1867, James Carter was charged with stealing some cake from Timson’s. He paid for a penny-worth of cake, but as soon as he left, Jane Timson “missed a lump of cake, and she called him back, and saw that he had got it under his smock frock. Defendant said he was very hungry”.[8] The fine he paid would have secured a lot of cake for James.

Knee breeches persisted with older and poorer labourers for many years after the introduction of “trowsers” in the 1820s; both types were of hardwearing materials such as buckskin, fustian, moleskin and corduroy. Trousers would be strapped up below the knee “to raise hems out of the mud and, allegedly, to prevent field mice running up the trouser legs”.[9] Gaiters or leggings would protect the lower legs.

In 1867, John Prior (age 56), a groom of Aldbury, was charged with stealing a pair of gaiters for which he was sentenced to seven years penal servitude. He maintained that the things were found in his basket and he didn’t recollect taking them. He had four previous convictions; he was transported for one of them four years previously and had returned. He was falsely accused in another case and begged for “mussey, because… he never would be found taking nothing, not never no more”, a string of double-negatives which carried no weight with the bench.[10]

Group of employees with poultry at Dwight’s Pheasantries

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK6199.32)

At Dwight’s Pheasantries, a group of employees are tending the chickens in their shirt-sleeves watched by a hatless foreman in his tie, long button-down overall and white gaiters. The variety of hats may depict the passing of fashions with the chap on the right in the ubiquitous flat cap, next to him a fedora-style hat with down-turned brim and the young man on the left in a felt trilby.

The older chap in the middle sporting a white moustache and straw hat wears heavy-duty trousers held up by braces, V-shaped at the top for ease of movement and with reinforced patches on the knees; they may have been in service for many years of “make do and mend”.

George Philbey, just days out of prison for burglary, was charged with stealing 196 pheasants’ eggs from Dwight’s. Nicknamed “Dickey bird”, Philbey was nabbed using evidence from the nails in his shoes corresponding to footprints found at the scene.[11]

Servants on country estates

The complexity of design in the embroidery of smocks reached a peak in the mid-nineteenth century.[12] Workmen’s smocks would not be so lavishly decorated as that of Mr Parkin the coachman. Servants in livery and smart modes of transport helped to flaunt the status of their rich employers.

Mr Parkin, coachman for Col. Smith Dorrien (1814-1879)

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK2788)

In the 1891 census, Colonel Alfred G Lucas was a contractor and tenant of Ashlyns Hall with a governess for his five children, a cook and nine female servants, three laundry maids, a butler, two footmen, a manservant, a valet and a coachman. The gardener Mr Alexander Higgins lived in a cottage on the estate with his family.

In the photograph below, at the centre back of the female staff, a lady wearing a high-necked dress and distinctive hat may have been the governess or housekeeper. Behind her the butler in a short dark (tailed?) jacket and waistcoat with watch chains, white shirt with wing collar and black tie is flanked by two smartly-dressed footmen.

Staff at Ashlyns Hall

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK4523.2)

Next to them is possibly the under butler, also dressed in winged collar and black tie, covered almost completely by a large white apron, protection whilst cleaning silver and preparing drinks. Beside him stands a bearded man who appears to be wearing a folded paper hat, neck scarf and a waist apron which he has tucked up over his waistcoat; he was likely a carpenter or painter whose cheap headgear helped to protect his hair from debris or paint. Seated in front of him is the afore-mentioned head gardener Mr Higgins, who in 1888 was secretary to the Chrysanthemum Society chaired by F.Q. Lane of Lane’s Nurseries.[13]

Two men on the left of the picture wear straw hats, one with knee-high gaiters perhaps signifying work with horses (a coachman perhaps?), the other seated with a dog who evidently could not keep still for the picture (the gamekeeper?). Next to him, the chap wearing the bowler hat and tie also has a long dark, perhaps leather, apron whilst the man and boy behind him wear ties and the popular round woollen peaked cloth caps formerly worn by sportsmen.

Gardeners “started as boys and grew old in the service of one or two gardens”.[14] Proving this statement, Jonas Bedford was buried in 1887 in the Baptist burial ground in Northchurch, having worked as the gardener for Mr Wadham L Sutton’s family at Rossway for 56 years.[15] In 1896, one of four names under consideration for the job of cemetery caretaker in Tring was George Batchelor, “aged 40, with a large family, who had been employed on the Rossway estate for nearly twenty years, nine years with Mr. C. Hadden, and ten years with Mr. G. F. McCorquodale.”[16]

Rossway garden staff outside orange house in 1906

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK2719_2)

Big houses like Rossway had teams of gardeners; their wages were 14/- (70p) per week. Noted on the back of the photograph above, “in the back row left was the brother of Joe Kempster. Jim Batchelor’s father (on the right with the side whiskers) died at Tring Lodge at the age of 91”. By this time, outdoor workers were wearing trousers with shirts and waistcoats. Evidently the working man’s peaked cloth cap was popular here, with a couple of bowlers to identify senior members of the team.

Women’s work wear

Being less visible than men in the records, it is harder to be certain of women’s work wear. In 1748, Pehr Kalm wrote in his diary “The entire domestic duties of the women folk in these parts consists of scarcely anything else than of preparing food… washing and scouring dishes and floors… washing clothes, and of expertly employing needle and thread”. He went on to say that their evenings were spent sitting idly round the fireplace and they left outside chores to their men folk.[17] However, Verdon in her study in praise of farmers’ wives found that they took responsibility for the dairy, poultry, pigs, garden and kitchen.[18]

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the basic working costume for women consisted of an ankle-length petticoat, leather stays and a low-necked dress over the top, with a large kerchief tucked into the front of the dress. Bibless aprons were essential.[19] Shawls remained common in country areas, masculine-style overcoats coming into female use from the 1870s.[20]

Fruit pickers at Lane’s Nurseries

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK5710)

Indoors, the hair was covered by a small cap, outdoors a straw hat would be placed on top. Later, this was replaced by a sunbonnet often with a frill or curtain to protect the neck and shoulders and stout shoes or boots would be visible below the hem of the dress.[21]

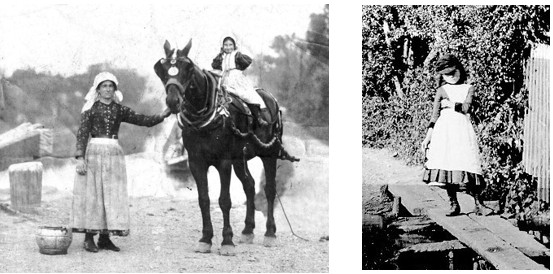

Woman in patterned dress, a washerwoman and Betty Leatherland

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK4543, BK4561, BK2754)

We are fortunate that local photographer William Claridge (1797-1876) left us several portraits of the men and women of Berkhamsted, though they are undated and only a few name the individual sitters. The woman pictured on the left above wears a white lace cap, a patterned dress with a dark coloured kerchief at the neck and the inevitable white apron.

Those who could afford it sent their laundry out to a local washerwoman. This sometimes provided opportunities for a little larceny on the side. In 1864, Sarah Potter (40) was charged with stealing two shirts belonging to William Norris on evidence produced by the local pawnbroker. Potter had been employed as a washerwoman by Mrs Norris and had given conflicting evidence at her trial, but “to the surprise of the whole court”, the jury found her not guilty.[22] The washerwoman in the picture above wears a lace bonnet, a patterned waistcoat over a shirt with rolled up sleeves and a white apron that could do with a wash.

The red hooded cloak, popular with country women, was rarer by mid-nineteenth century “although some elderly women retained the beloved garment worn throughout their lives”.[23] Betty Leatherland (born 1763) was a gypsy who lived rough on Berkhamsted Common, said to have laboured on a farm at the age of 110; she still wore the red cloak provided by Col. Smith Dorrien.

Canal workers

By 1823, John Hatton had taken over the boat yard at Castle Wharf which he ran with his wife Elizabeth. Her father Thomas Monk founded a dynasty of boat builders with his fleet of narrowboats in the Black Country, attributed “monkey boats”. Boatmen would live with their families on narrowboats plying between London and the Midlands. They lived largely nomadic lives and had their own traditions and distinctive bright-coloured scarves and gaudy dresses.[24]

While her husband might wear a velvet cap and waistcoat, the mother pictured below passing through Berkhamsted wears a colourful dress covered by a large white apron with an elaborate white bonnet. Her smiling daughter looks to be following in her mother’s footsteps. The girl on the right is likely from a bargee’s family. She wears a peaked cap and a bibbed white apron over a knee-length dress with long boots.

A boatman’s family

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK702.1 & BK5583)

Trades and crafts

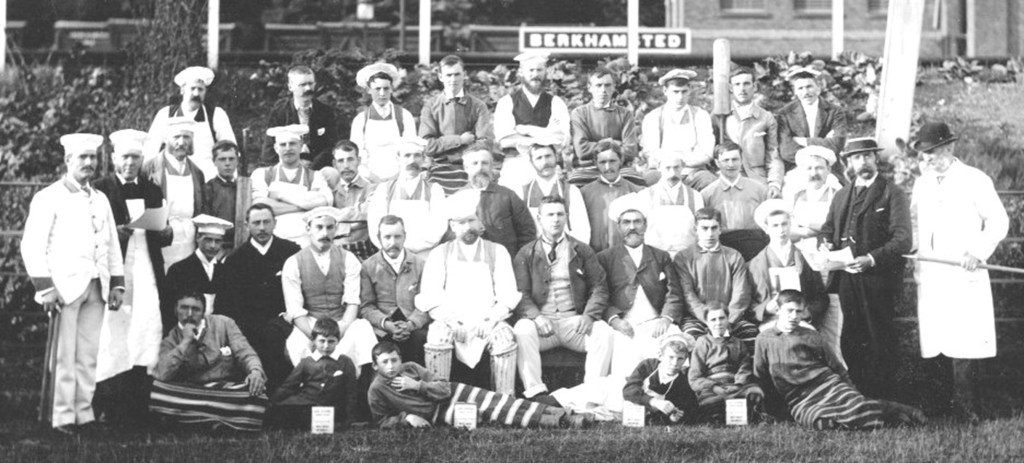

“For sheer old fashioned charm, the butchers must take the prize… they stick to the old-fashioned straw hats and blue and white striped aprons.”[25] One straw hat is on display in the picture below and some striped aprons. Long aprons could be worn buttoned to overalls at chest height. To protect forearms and cuffs, fishmongers wore oversleeves, probably waterproof like their aprons. Milkmen also wore blue and white aprons, which were superceded by short nylon overall coats in the 1970s.[26]

Butchers v Bakers charity cricket match (undated)

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK5203)

For cleanliness in the kitchen, local bakers favoured white outfits from head to toe: short-sleeved shirts, long aprons and baker’s hats (also called toques) made of lightweight material, the rim tight to the forehead to retain the hair and the top of it rising in height to indicate seniority.

Woodenware was a thriving local industry in Berkhamsted, evolving from individual workshops to steam saw-mills.[27] Alongside these were boat builders, coach builders and coopers supplying barrels for the local brewers. Pocock’s forge was the first workshop to greet travellers on the main road from London. Walklate’s saddler’s shop with its “manly tang of leather” was opposite Percy Millen the shoemaker who had taken over from George Loader in Graball Row. For these craftsmen, basic working clothes were overlaid with further protection, such as leather aprons and hand leathers to guard the palms when stitching stiff materials.

Note the long aprons and the variety of head gear for Pethybridge’s workmen in the picture below. There are high-crowned billycock hats, bowlers and is that a deerstalker the ostler is wearing with ear flaps tied on top? The women of the family notably do not wear aprons like the servant on the right whose hair is covered in a close-fitting cap.

Pethybridge the coach builder

Source: BLH&MS (DACHT : BK10851)

After a break-in at Mrs Glennister’s beer shop in “a bit of a village” down Winkwell, thieves got away with three coats, a pair of trowsers, 3lbs tobacco, 10s. in coppers, four cotton handkerchiefs and a billycock hat. They hid the clothes in a stable loft at Bank’s Mill and the tobacco and money in a dung heap. The three prisoners were found at the Red Lion Berkhampstead. Verdict, guilty. Two of them were sentenced to ten years’ transportation, the other to 12 months’ imprisonment with hard labour.[28] The moral of the story is only nick clothes if you want to travel far far away (indeed one of the prisoners expressed a wish to be transported) and was the dung heap hiding-place the origin of “filthy lucre”?

Linda Rollitt

[1] Wallis, K., ‘The Mantle Factory’, Chronicle, vol.VI (2009), pp.22-31

[2] Birtchnell, P., ‘Berkhamsted’s Ancient Statute Fair’, Berkhamsted Review (Oct 1942). Presumably included a race in a one-horse covered jingle cart.

[3] Rollitt, L., ‘The Bloody Code Sentencing Options and Berkhamsted’, Chronicle, vol.XXI (Mar 2024), p.65

[4] Greene, R.G., ‘Fashion’, The New Imperial Encyclopedia and Dictionary (1906), p.259 (forty volumes)

[5] Shrimpton, J., Fashion and Family History (2020)

[6] OBP, ‘Benjamin Thompson, Richard Gibbert’, ref: t18030112-49 (12 Jan 1803)

OBP = Old Bailey Proceedings online 1674-1913

[7] Bucks Advertiser (1 Sep 1866)

[8] Herts Advertiser (10 Aug 1867)

[9] Shrimpton, Fashion

[10] Herts Guardian (22 Oct 1867)

[11] Bucks Herald (10 May 1884)

[12] Hall, M., ‘Smocks’ Shire Album 46 (1979), p.3

[13] Bucks Herald (10 Mar 1888)

[14] Lansdell, A., ‘Occupational Costume and working clothes, 1776-1976’, Shire Album 27 (1984), p.26

[15] Bucks Herald (13 Aug 1887)

[16] Bucks Herald (10 Oct 1896)

[17] Mead, W.R. Pehr Kalm: A Finnish Visitor to the Chilterns in 1748 (2003) pp.122, 127

[18] Verdon, N., ‘Farmers’ wives and the farm economy in England, c. 1700–1850’, Agricultural History Review, vol.51, part 1 (2003)

[19] Lansdell, Occupational Costume, p.8

[20] Shrimpton, Fashion

[21] Lansdell, Occupational Costume, p.9

[22] Herts Guardian (12 Jan 1864)

[23] Shrimpton, Fashion

[24] Lansdell, Occupational Costume, p.31

[25] Cook, J., Berkhamsted Review (Jan 1991)

[26] Lansdell, Occupational Costume, p.29

[27] Birtchnell, P., ‘The Town’s Old Woodenware Trade’, Berkhamsted Review (Jun 1943)

[28] Herts Guardian (17 Jul 1852)