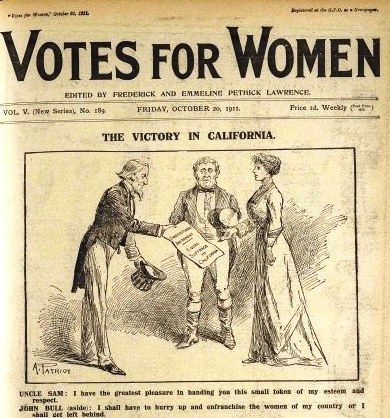

A cartoon in the Votes for Women magazine in 1911 depicts women’s victorious quest for the vote in California, whilst England in the guise of John Bull says “I shall have to hurry up and enfranchise the women of my country or I shall get left behind”.

Votes for Women magazine, 20 Oct 1911

California became the sixth state to give women an equal vote with men nine years before the 19th Amendment enfranchised women nationally. After World War I in 1918, about 8.4 million British women aged over 30 with the right property or academic qualifications gained the vote, but those between 21 and 30 had to wait another ten years.

The 1832 Reform Act had granted the vote to property-owning men and this was extended to working-class men in 1867 and 1884. Meanwhile, the women’s suffrage movement was gaining momentum with critiques about the ideology of separate spheres: men presiding over public life and women maintaining the home.[1] The campaign became militant in 1903 when Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst led the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in protests that included breaking windows and chaining themselves to railings.

In 1909, the WSPU had reached Chesham with open air meetings advertised in chalk on brown paper “Votes for Women ; Meeting ; Broadway ; Noon ; Wednesday, August 25th.” Three ladies argued the case for women to vote if they had similar qualifications as men, for instance if they owned property. Women were sent out to canvass for men, they helped men in battle and even fought beside them in the Boer War and yet they had no voice in Government. Many men could not write or had no interest in politics yet they had the vote. The WSPU women also defended the militant methods of the Suffragettes. They would never get the vote using methods of the last fifty years; there had to be agitation.[2]

Mrs Humphry Ward of “Stocks” in Aldbury was a novelist and President of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League.[3] She believed in the broadening of education suited to the female role rather than the “antiMan” agitation favoured by the “New Woman” as she was called in the 1880s.[4] Mrs Ward drew up a “Protest against the extension of the Parliamentary Franchise to Women” because she believed in the separate spheres ideology. She argued that women did not work in the Army and Navy, heavy industry or commerce and finance, so why should they influence policy in those areas? She also maintained that the existing male Parliament dealt with women’s reasonable grievances.

However, she was in favour of women sitting on County or Borough Councils and other similar bodies (such as the 200 boards of guardians) concerned with the domestic and social affairs of the community. She called this the “enlarged housekeeping” of the nation. Service, not rights was her watch-word.

Mrs Humphry Ward at home

Photograph by JT Newman, Berkhamsted

Source: The Sketch, 10 Sep 1902

There was some push-back against anti-suffrage logic. When she became chairman of the newly-formed Local Government Advancement Committee in 1912, Mrs Humphrey Ward appealed for qualified women to help their own sex, children and the nation. She bemoaned the prejudice against women joining local bodies but did not recognise the same prejudice against their full enfranchisement. She attracted adverse comments by making anti-suffrage opinions a “qualification” for securing her support, with some opining that her organisation did not deserve success.[5] Mrs Ward also entered into spirited debate with Millicent Garrett Fawcett, leader of The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) in the Times and reported in the Votes for Women paper.[6]

Lady Churchill goes electioneering with Sir Winston

Source: The Sun on Sunday, 21 Nov 1934

In an article Suffragettes on the Warpath, we are left to wonder what Clementine Churchill thought about her husband’s views about “the intrusion of women into public affairs”. Nevertheless, “Her arrival at [his] side on political platforms had a subduing effect on Suffragettes who up to then seemed to make Churchill their special target.”[7] As a woman contributing in a man’s world of politics (electioneering and constituency work), it is likely she sympathised with many of the aims of the Suffragette movement. She attended the big Bow Street trial of leading activists and followed the proceedings intently. However, Clementine deplored the methods the Suffragettes used to gain their ends. When she returned to her old school in Berkhamsted, her advice to the girls maybe gives an insight into her dealings with her irascible husband: “If you find yourself in competition with men, never become aggressive in your rivalry… She who forces her point may well lose her advantage. You will gain far more by quietly holding to your convictions. But even this must be done with art, and above all with a sense of humour.”[8] [9]

Women had the support of some “Suffragettes in Trousers” such as Lord Lytton. In 1911 there was a public meeting in Berkhamsted Town Hall in support of the campaign of the Conservative and Unionist Women’s Franchise Association in favour of the Conciliation Bill that was due to be brought before Parliament in the following year. Meetings had been held in the town and neighbourhood both by the “pros” and the “antis”. In this meeting, Geoffrey Chubb (of the lock and safe making family) occupied the chair. A resolution was proposed “That this meeting approves of the Conciliation Bill, which would give votes to women householders, and pledges itself to use every effort to secure the passage of the Bill next year.” The resolution was carried with acclamation.”[10] The Bill failed to pass in 1912 with blame shared between militant tactics and the Asquith government’s disregard of women’s suffrage.

In 1913 there is evidence that some local women were involved in destructive activities designed to draw attention to their demands. In February, there was a suspicion that sixteen telephone wires had been cut by suffragettes, disrupting trunk calls from the locality to London.[11] In September of the same year, a wheat rick was destroyed by suffragettes near Berkhamsted and attempts were made to fire other ricks. On a gate close by were chalked the words, “Votes for Women,” and a paper was found on which was written the misquotation, “Those that walk in darkness shall see a great light.” The police found at other ricks that a candle had been lighted in a cigarette box and placed under a flower-pot, while a piece of soaked tow led from it into the rick, but the candle had gone out. The destroyed rick, which contained a remarkably fine crop of wheat, was insured.[12]

Acts like these no doubt prompted a shift in attitudes to women’s role, for better or worse, but recognising that they would have an integral part to play in the war effort, “Within hours the suffragettes declared that their own aims were entirely shelved and that they would instantly convert their organisation to the nation’s service”.[13] Historians are undecided whether destructive suffragette activity brought about the change in the voting laws, or whether they were rewarded for their efforts during the war.[14]

Linda Rollitt

[1] Shoemaker, R., ‘Gender Roles in the Eighteenth Century’, The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Gender.jsp#genderroles (accessed Mar 2025)

[2] Buckinghamshire Examiner (27 Aug 1909)

[3] Beorcham, Berkhamsted Review (Jul 1952)

DHT holds copies of all her books. Two of these have anti-suffrage themes: Delia Blanchflower (1915) and The Testing of Diana Mallory (1910)

[4] Trevelyan, J.P., The Life of Mrs. Humphry Ward (2012), pp.224-245

G.M. Trevelyan and his wife Janet Penrose, daughter of Mrs. Humphry Ward, lived for several years in Kings Road Berkhamsted.

[5] Reading Standard (10 Aug 1912)

[6] Votes for Women (22 May 1914)

[7] ‘Suffragettes on the Warpath’, The Sun on Sunday (21 Nov 1934)

[8] Ibid.

[9] Read more about Clementine’s old school in Sherwood, J., ‘Early Days of Berkhamsted School for Girls’, Chronicle, vol.15 (Mar 2018) and a blue plaque at 107 High Street indicates Clementine Hozier’s childhood home.

[10] London Evening Standard (25 Oct 1911)

[11] Hemel Gazette (Feb 1913)

[12] Burnley News (Sep 1913)

[13] Adam, R. & Roberts, Y., A Woman’s Place: 1910-1975 (1975)

[14] BLH&MS, ‘Women’s War Work’, Berkhamsted in WWI (2017), pp.57-66