One of the first performances of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan was staged especially for the Llewelyn Davies boys, one of whom was ill, at Egerton House in Berkhamsted High Street. Barrie always acknowledged that the boys’ free-spirited youth was the inspiration for his play. “I made Peter by rubbing the five of you together, as savages with two sticks produce a flame,” he wrote on the dedication page of the printed version of the play.

Source: Photograph by J.M. Barrie[1]

The boys’ first meeting with J.M. Barrie was described in the press:

… a bright little family of children played in the sunshine in Kensington Gardens, Sir J.M. Barrie came strolling by and played with them. He was a man in years, and a distinguished man in renown, but, while he played with the children, he was as one who never grew up, and they grew to know him and to love him.[2]

Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies, who had become friends of Barrie, lived at Egerton House for two or three years, partly because they thought the country air would suit their five sons (George b.1893, Jack b.1894, Peter b.1897, Michael, b.1900 and Nicholas b.1903), and because they could send them to Berkhamsted School as day boys.

A snippet of information about the older boys’ school days appears in an early copy of the Berkhamsted Girls’ School magazine, the Chronicle:

We went to the Big School in the High Street to play on the see-saw and the giant slide. ‘Peter Pan’ and his two brothers were brought every day by their mother, Sylvia du Maurier (Mrs. Llewelyn Davies) They wore blue-green djibbahs with thick blue socks.[3]

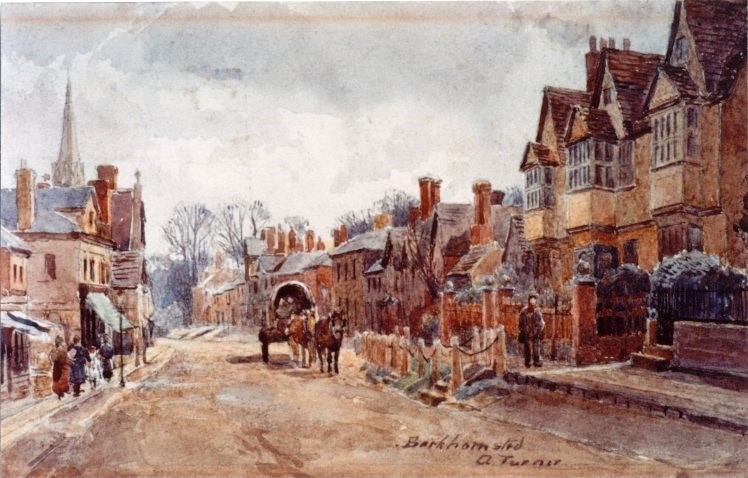

The rambling Egerton House must have been the scene of many adventures for these imaginative boys. We get an appreciation of the nature of this “fine specimen of Elizabethan architecture” from sales details prepared for an auction held at the Kings Arms on 23 Sep 1895:

In the attic were four bedrooms… with three staircases to the first floor [which] had six rooms, comprising two large bedrooms… a boudoir, a saloon… two visitors’ rooms, spare room. Two staircases led to the ground floor; on one was a bathroom and W.C. On the ground floor was the entrance hall with large arched chimney corner, fireplace, oak floor. Doorways leading to various rooms and passages were decorated with carved oak figured mouldings. To the right was the dining room… to the left the drawing room. Behind was the conservatory facing the garden and opening on to Billiard Room. Two other rooms connected to the hall, for housekeeper’s room or domestic offices. There was a kitchen and back kitchen, pantry, larder and wood and coalhouse. The basement had cellarage divided into five compartments. Out offices included two WCs, courtyard, wood house, garden house. Stabling abutted on to the road, had a courtyard, with entrance gates… comprised a stall and two loose boxes with loft over. There was also a coach house with loft over and harness room. The garden extended for a considerable distance from the back of the house and was not overlooked.[4]

Due to his mother’s flair for interior decoration, Peter Davies wrote that the house “revealed itself, when you went in, not in the least as a museum or ‘period’ affair or a place to make you catch your breath at its exquisite beauty, but as a gracious, happy, pretty, comfortable house”. He particularly remembered “That garden, with its plum trees on the walls, and luscious mulberry tree, and lovely pale wisteria by the stable, and the little orchard at the end… the big fir-tree which grew on the bank at the back of the lawn”.[5]

J.M. Barrie, who owned Black Lake Cottage, on the outskirts of Farnham in Surrey from 1901 to 1908:

… invited the Llewelyn Davies family to join him one summer at his weekend retreat. There are photographs in the book The Happy Garden by Barrie’s wife, Mary Ansell, showing the children playing pirates in the gardens and nearby Bourne Woods, including one of the boys, Michael, dressed very much like Peter Pan.[6]

In 1904, Barrie wrote to the boys’ mother Sylvia from Black Lake Cottage to tell her he was sending a pony and “writing to Windover [sic] to hurry the cart… Yoicks, gee, whoa, there. Your loving, J.M.B.”[7] Peter wrote: “I imagine the lavish gift of a pony and cart – a sort of governess cart, as I recall it – was bestowed as a tangible recognition of indebtedness to ‘Sylvia and Arthur Llewelyn Davies and their boys (my boys)’ for their contribution to The Little White Bird and Peter Pan.”

In 1906, Barrie wrote in affectionate terms to Peter:

Hurrah for your birthday. Nine years ago the world was a dreary blank. It was like the round of tissue paper the clown holds up for the lady in the circus to leap through, and then you came banging through it with a Hoop-la! and we have all been busy ever since.[8]

Following the tragic death of Arthur on 19 Apr 1907, life at Egerton House went on somehow. Peter was at Berkhamsted School, and Jack went to Osborne. Later that year, with Barrie’s help, Sylvia left Egerton House and returned to London.[9]

Meanwhile, early showings of Barrie’s Peter Pan that year were getting some mixed reviews. Some in the audience laughed through several scenes, but were forgiven by one reviewer as Barrie was breaking entirely new ground; the mind had to be “attuned to a particular key” to appreciate its merits:

J.M. Barrie must possess an enviable intimacy with children and child life. Without this knowledge… he could never have created a fairy tale possessing as strong an attraction for folk of mature years as [for the young]. Granted the ability to comprehend a child’s powers of make-believe, and then you will enjoy to the full the wonderful world inhabited by the strangest beings that dramatist has ever fashioned. Back all this up with much that is absolutely true to nature, and you will begin to comprehend the full extent and scope of this fantastic play, with its rich humour, its deep paths, its exciting episodes, its sensational adventures, and its melodramatic touches.[10]

In the summer of 1910, when Barrie was back at Black Lake Cottage, he wrote to Sylvia, knowing that her health was failing (she had lung cancer):

I hope you are feeling pretty well, but I don’t believe it, and that saddens me. At all events I can trust to the others being lusty and am looking forward to your being here with George… Yours, J.M.B.

Of this letter, Peter Davies wrote that if that trip to Black Lake Cottage had taken place, it was the last visit by any of the family to the scene of “The Boy Castaways”. It was at that time that the gardener informed Barrie of his wife’s affair with the much younger Gilbert Cannan, which led to their divorce. Peter speculated whether Sylvia knew of the affair:

Had [Sylvia] seen it coming? I don’t know what the relations were between her and Mary Barrie. That she must have had thoughts… about its possible effects on her own and our future, goes without saying. Any situation involving J.M.B. was inevitably peculiar. That S[ylvia] found him a comforter of infinite sympathy and tact, and a mighty convenient slave, and that she thankfully accepted his money as a gift from the gods to herself and her children – all that is clear enough.[11]

More tragedy was to come when two of the boys died young. George Llewelyn Davies was killed in action aged twenty-one, on 15 March 1915, Second Lieutenant in the 4th Battalion Rifle Brigade. Michael Llewelyn Davies drowned with a close friend in Oxford University in 1921.

Egerton House was demolished in 1937 to make way for the Rex Cinema. Birtchnell wrote:

On seeing pictures of Egerton House, many people say how sorry they are that such an attractive Elizabethan mansion was destroyed. An effort was, in fact, made to save it [including asking Barrie for help, but he was too ill to intervene], but thousands of pounds would have been needed to bring it into a reasonable state of repair after many years of neglect, during which it had been overrun by cats, monkeys and other animals. The last owner was somewhat eccentric![12]

Miss Buchan, daughter of the late Rev. John Buchan, spoke of:

… the most conspicuous literary success of the age, J.M. Barrie… Like his own ‘Peter Pan,’ he never seemed to grow up. He was the eternal boy, plucking at the skirts of this old world, and appealing to it to stop and play with him.”[13]

Sir James Barrie died aged 77 in a London nursing home. At his funeral in Kirriemuir, the cortege included many famous people representing all classes. The mourners included Peter Davies and his brothers, described as “adopted sons of Sir James”.[15]

This story does not end well. At Eton, Peter Davies had endured taunts about his perennially juvenile namesake and later felt he had been exploited by Barrie, especially as he had been cut out of his will at the last moment. By 1960 Peter was a chronic alcoholic and suffered from emphysema. His tragic demise, throwing himself under an approaching train, was described in the press as “The boy who never grew up is dead”. Even in death, he could not escape the shadow of Peter Pan.

[1] The author died in 1937, so this work is in the public domain.

[2] Whitby Gazette (26 Mar 1915)

[3] Sherwood, J., ‘Early Days of Berkhamsted School for Girls’, Chronicle v.XV (Mar 2018), p.37-38

[4] Sherwood, J., ‘Egerton House, a small Elizabethan mansion’, Chronicle, v.II (pp.23-26)

[5] Dunbar, J., J M Barrie The Man Behind the Image (1970), p.139

[6] ‘Surrey’s very own Neverland’, Times (3 Aug 2018)

[7] Dunbar, Barrie, p.143

[8] Ibid, p.148

[9] Ibid, p.162

[10] Bristol Times and Mirror (30 Apr 1907)

[11] Dunbar, Barrie, p.180

[12] Birtchnell, P (writing as Townsman), Berkhamsted Review (Jan 1972)

[13] Fife Free Press, & Kirkcaldy Guardian (20 Jan 1923)

[14] Arbroath Herald (1937)

[15] Arbroath Herald and Advertiser for the Montrose Burghs (25 June 1937)