In the first edition of the Chronicle in Mar 2003 Ann Nath discovered “the background of the events and characters that were associated with the area then known as The Manor of Maudelyn 1272-1485”.[1]

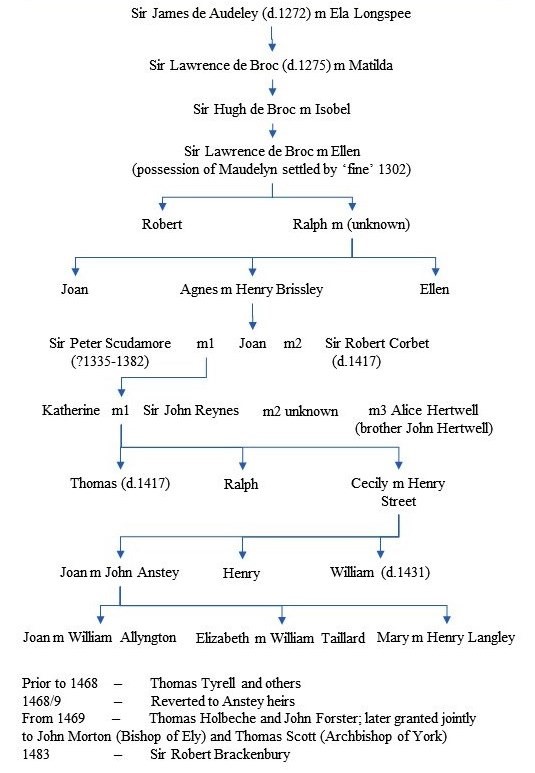

Ann was able to trace early occupants of the Manor using the inquisition of Ware 1431 in the reign of Henry VI and she detailed the succession in her article, including a diagram of the connections (redrawn above).[2] This article seeks to build on Ann’s project (which she conducted with Eric Holland and Jimmie Honour) and investigate the people who lived and worked in and around the Manor of Maudelyn since 1485.

First, where is Marlin Chapel? Percy Birtchnell gives us directions via a pathway which is no longer available due to the new A41: “…go to the top of Cross Oak Road, turn west along Shootersway for a short quarter of a mile, and then left down Gallows Lane, signposted ‘Bridlepath’. From the valley take the forward path… passing on your left moated Marlin Chapel Farmhouse, on the site of the ancient manor house. You now enter a small meadow and on your right you will see Marlin Chapel, now so overgrown that little of the ancient, broken walls is visible.”[3]

When intact the chapel itself was nearly 60 ft long and 19ft wide, with walls of worked Totternhoe stone and flint 3ft thick. Existing buildings on the site date from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[4] A drawing of 1878 shows buildings in the north eastern corner of the moat platform. Timber-framed buildings with jettied crossing, possibly of late medieval date, have been located in the area. A surviving section of chequer-work wall and a cellar under one barn are likely remnants of these buildings.[5]

J.W. Cobb wrote of “the ruin called Marlin’s Chapel… probably the remains of the domestic chapel of the adjacent house, dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene, of which the modern name is a corruption. Marlin’s is called a mesnalty [estate of a mesne lord] in Northchurch parish, and in Dean Incent’s rental-book rent… is paid to the ‘Lord of Magdalene’”.[6]

Percy Birtchnell (as Townsman) wrote of “the remains of this remote chapel-in-the-fields, which was built in the 13th century by the lord of the little manor of Maudelyns (Magdalen). The manor house stood on the site now occupied by Marlin Chapel Farm, and much of the surrounding moat survives to this day, sometimes with a little water to dissuade invaders!” He continued: “the lord of the manor, in his remote home near the parish boundary, thought it better to worship in his own chapel than to trudge through the mud to the parish church”.[7]

Taking the story forward from Ann’s chart, Sir Robert Brackenbury died with King Richard III at Bosworth. Following various actions in the Court of Chancery, Robert Morton secured possession of the Manor from other claimants (Whittingham and Verney families) who only released their claim in 1512-13. The Mortons maintained possession until 1556 when it was conveyed to John Dell of Leyhill.[8]

In the seventeenth century the manor was “dismembered and sold in small parcels to divers men, who now pay rent and perform their services for the same at every Court held for the Honour and Manor of Berkhamsted”.[9] Although the manor rights were lost long ago, the name lived on in Marlin Chapel Farm and in 1728, antiquary Salmon said the old chapel was used as a malthouse.[10]

A well-known name in Berkhamsted, James Wood “came originally from Marlin Chapel Farm and in 1826, whilst living at Monks Cottage in the High Street rented the yard [now Woods of Berkhamsted] from Berkhamsted School. His reputation grew as he made and repaired such diverse items as estate gates, candle snuffers, meat safes, fire guards and rat traps for many of the large houses and estates in the area.”[11]

The 1841 census shows that William Hollingshead was working at Marlin Chapel Farm. Meanwhile, Charles Prudames was a farrier and ironmonger living in Berkhamsted High Street. By 1851 Charles was a veterinary surgeon and his son Alfred followed that profession later. Alfred married William’s daughter Lucy in 1864 and another daughter Jane’s second husband was Alfred’s uncle David William Prudames, who carried on his father’s ironmongery trade. These marriage alliances would have helped to ensure that the family businesses were retained for the next generations.

In 1855, Marlin Chapel Farm was for sale on behalf of Mr. William Derisley, who was to leave the farm the next Michaelmas. It was described as adjoining Marlin’s Farm which was also to be sold by direction of Mr. W. Redding, who was leaving.[12] In 1857, Colonel Smith Dorrien sought to recover £24 15s from Derisley. The Colonel had paid the outgoing tenant Mr Hollingshead for wheat straw which he left on the farm on quitting it. Derisley as the incoming tenant had paid the same amount in spring 1850. When he left in Sep 1855, he sold the wheat and kept the proceeds instead of dividing it according to the custom of the country. The Colonel won the case and was awarded £17 damages.[13] In 1861, William Derisley was victualler at the Red Lion in Berkhamsted.

In 1861, “a bright bay mare was stolen from a stable at Marlin Chapel Farm, the property of Mr. Jakeman, farmer.”[14] He quit the place in 1870 with the sale of “the live and dead stock, comprising 7 Cart Mares and Colts, 8 head of cow stock, 50 ewes and lambs, 20 tegs and other sheep, 16 fat and store pigs, a variety of useful farming implements, and other effects.”[15]

J.T. Newman, photographer of Berkhamsted, describes what must have been Marlin Chapel Farm, which evidently provided turkeys for Christmas: “Some of these farmhouses must be centuries old, and make ‘quite a picture’ with their quaint half-timbered gables in many cases overhanging the stock-yard. In the one illustrated the upper rooms of the house were built over a gateway, which formed a shelter for the cattle, and the whole block was surrounded by a half-dried moat, while near by stood the ruins of an ancient chapel, the walls of which were crumbling from the ravages of time, but showed from their immense thickness that in the ages past the place was of some importance.”[16]

Marlin Chapel Farm was for sale in 1909, then part of Mr. T.A. Dorrien Smith’s Haresfoot Estate. “Messrs. Brown and Co. held… a sale of farming stock, corn, hay, &c., the property of Messrs. G. and W. Bedford, who are leaving and going to a farm at Charteridge. There was a large gathering of agriculturalists at this outlying place, and good prices were realised. Not long since a new farmhouse was built (inside the deep moat which formerly enclosed the moated grange or manor house).”[17]

In 1937, the farm was again for sale when Mr. W.H. Thorn retired, with stock and farming equipment including: “Farm Waggons, Farm Carts, Turnip Cutters, 5½ H.P. Amanco Engine, Harrows, side delivery Rakes, Ladders, Rick Cloth, Root Pulpers, Scales and Weights, Sack Lift, Chaff Cutters, Pig Troughs, Harness, Self-Binder, Ploughs, Rolls, Mowing Machines, Poultry Houses, etc., and a few lots of Household Furniture”.[18]

In 1942, Marlin Chapel Farm was let on the Rossway Estate, comprising 170 acres, chiefly arable land, with a good house, two cottages and buildings.[19]

In a fascinating audio recording, which brings us into the twentieth century, Graham Dell and his cousin Leslie King talk of their experiences of living at Marlin Farm off Shootersway in the 1930s-1950s. Graham was born in Hemel Hempstead on 12 Jun 1941 and lived at the farm until 1959. Leslie was born in 1932 in Hawridge; his family moved to Heath End and left in 1958. Graham’s family moved into Marlin Farm in 1929 as tenants from Rossway Estates, whilst previous owners, the Puddifoots, moved to Heath End.

Marlin’s was a mixed farm and self-sufficient, with pigs, chickens, arable and vegetable plot. Travel was via pony and trap; there was no car until after the war. Milk was collected by Express Dairy and taken to London. The blacksmith was Kempston Brothers by the canal and later at Swingate Lane. There was no electricity; they used paraffin oil lamps, then Aladdin lamps. In the 1950s, water mains were constantly bursting. There were two or three wells on farm, one in the garden, another in one of the yards with a pump and five ponds with good water. There was no mains sewage or septic tank; they used the pond called the Gooseberry with an overhanging cherry tree from which they used to harvest cherries despite the risk of falling in. Finally, the pond dropped about six feet and it had to be filled in. Graham had a crystal radio set. They replaced horses with a Fordson tractor in 1956. Leslie said they never locked the doors; the postman would come in and sit down for a cup of tea.

Land Army girls, billeted in Northchurch, helped with thrashing on the farm in the war, along with Germans Prisoners of War. During the 1940 blitz a bomb killed several calving heifers. The explosion was heard from two miles away in Heath End. It was well into 1960s when compensation finally arrived. A time-bomb in the ten-acre field went off six weeks later.

Leslie recounted the story of their grandfather Harry Dell’s accident in 1943 which resulted in his death: “Unloading sheaves of corn, we got off the rick, started the tractor and the ladder fell off. Grandfather was found on the concrete floor with a fractured skull”.

Graham recalled the time when he ploughed his Ingersoll watch into the ground and five years later ploughed it up again. Leslie used to drive the sow from Shooters Way Farm down Pea Lane to the bull at a small holding there. On the back way to Marlin Farm, there were two cottages. As his father was driving the sow, she walked straight into the front door of one of the cottages and he had to get her out again.

When the Rossway tenancy finished, the Dells moved out. They had to pay £500 dilapidation charges, even though it was ten times better when they left it. Home Farm was like a show farm with its own workers but when the old lady died, her nephew ground it down and doubled the rent.

In 1971, Birtchnell reported that “Another landmark has gone – Marlin Farm. This was the one we saw from Shootersway, at the end of a track which started between the tops of Durrants Lane and Bell Lane. The house was vacated some years ago, and with various outbuildings it quickly fell into disrepair, aided by a fire and much vandalism.”[20]

The remote Manor of Maudelyn supported a small community from the thirteenth century, even providing a small chapel to save a long muddy walk to church. A moated farm rose from the ruins of the manor house and an adjoining farm proved self-sufficient in times of war.

[1] Nath, A, ‘The Manor of Maudelyn, 1272-1485’, Chronicle, vol.I (2003), pp.10-15

[2] The succession of owners is also described in Victoria County History, ‘Parishes: Northchurch or Berkhampstead St Mary’, A History of the County of Hertford, Volume 2 (1908), pp.245-250

[3] Birtchnell, P., Berkhamsted Review (Apr 1983).

[4] Hertfordshire Archaeological Trust (H.A.T.), Archaeological Report (1997)

[5] H.A.T., Archaeological Report (1987)

[6] Cobb, J.W., Two lectures on the history and antiquities of Berkhamsted (1855)

[7] Birtchnell, P., Berkhamsted Review (Sep 1970)

[8] Pries, D., ‘The Manor of Mawedelyne, Hertfordshire’, Herts Past & Present, Issue 23 (Spring 2013), pp.25-28,32

[9] Chauncy, H., The Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire (1700), sponsored by John Egerton, the Third Earl of Bridgewater

[10] Salmon, Nathaniel, The History of Hertfordshire (1728)

[11] Van Heems, B., Berkhamsted Review (Apr 1996).

[12] Bucks Chronicle & Bucks Gazette (18 Aug 1855)

[13] Bucks Herald (15 Aug 1857)

[14] Bucks Herald & Bucks Gazette (29 Jun 1861)

[15] Bucks Herald (18 Apr 1870)

[16] Newman, J.T., Sketch (Sep 1898)

[17] Watford Observer (16 Oct 1909)

[18] Bucks Herald (17 Sep 1937)

[19] Bucks Herald (9 Oct 1942)

[20] Birtchnell, P., Berkhamsted Review (Apr 1971)