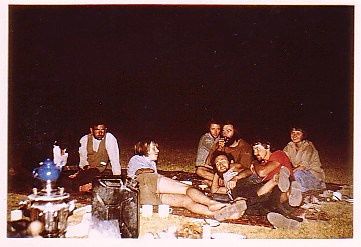

The Shah still occupied the Peacock Throne when our team of cavers from Oxford Polytechnic enjoyed the hospitality of a young landowner in his lemon grove in the heart of Iran. I had never been abroad and here I was with six hairy men on an expedition to explore the limestone caves of the Zagros Mountains. It was our third week on the road and the village headman, or Hadji, had invited us for our first decent meal of the trip. We lounged on a sumptuous Persian carpet beside a Nomad’s tent, the sky was dazzling with stars, a bubbling samovar gleamed and the air was filled with the enticing smells of meat and spices.

It was an abrupt awakening the morning after, when Derek (our leader) cried out in pain, the consequence of unfamiliar food on a delicate stomach. For the next few days, I watched in trepidation as four erstwhile strong men retched and writhed, delirious with pain. “A chain is only as strong as its weakest link,” I had been told – I thought they were talking about me, but I was the one washing out sick-bowls!

Though our team was substantially weakened, we limped on to our next destination near Malayer, about 200 miles from the capital city of Tehran. Through the barren countryside, the local women would amaze me with their resilience; separating a few edible grains from a haze of chaff, or patting donkey dung into briquettes for winter fuel. In the villages, there would be an occasional shop where we could buy drinks or a melon. It was odd to see pictures of Jackie Onassis on the walls, a reminder of the world outside this remote country.

We spent many hot and exhausting hours trudging in the hills and peering into every crevice, before we decided that our method of finding caves had to be refined. We would drive into a village and stop the Land Rover, bedecked as it was with sponsorship stickers. Within seconds, we would be surrounded by crowds of people; an intensely unnerving but exhilarating experience. Curious urchins would take up personal space and share their fleas with a smiling “Hello, Mister” – and pinch the stickers. Venerable citizens would climb off their bicycles for a closer look.

We had been told that ‘ghar’ meant ‘cave’ in Farsi (though we later learned it meant ‘hole’), so we would energetically mime climbing mountains and diving down holes to the accompaniment of ‘ghar, ghar’. Though most of the population were entirely bemused by this spectacle, we would somehow succeed in persuading some of the locals to hop on to the bonnet of the vehicle and show us the way to the caves. Off the beaten track, we would often have to disembark and hang on to the side of the Land Rover because the pitch in the dirt road was so steep – it was rather like sailing, but with choking clouds of dust billowing in our wake.

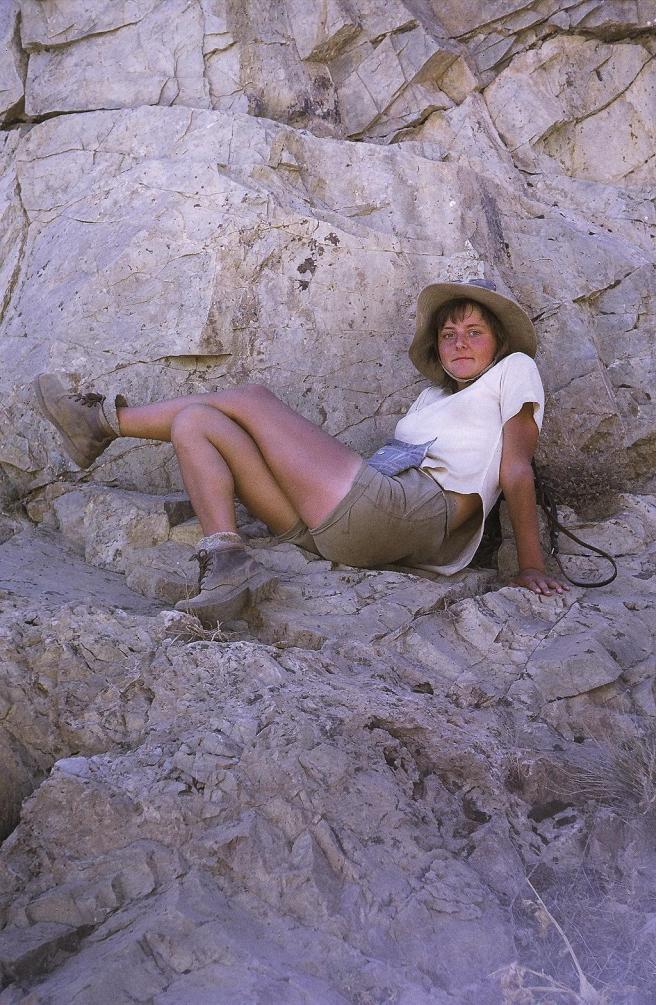

Our caving areas were, by necessity, high in the Zagros Mountains. Our base camps were at an altitude of 8,000 feet, so we were struggling to breathe; it was 40 degrees C, the dust settled on everything and water was in short supply. Sterilising tablets were essential to make the water drinkable (though it tasted disgusting) and there was none to spare for washing ourselves or our clothes. Oddly, we didn’t seem to mind – we each had a pink ‘Mum’ roll-on deoderant! Four of us slept cross-ways on a Lilo built for two. This was preferable to using our single Lilo which kept deflating, or scrunching up on the bottom-narcotising seats of the Land Rover.

I’d like to say that we greeted each day with Omar Khayyam’s poetry: ‘Awake! For Morning in the Bowl of Night…’, but the truth is that most mornings, there was a weak refrain of ‘Here comes the sun, do-be-do-be’, followed by a dollop of stodgy porridge and a cup of tea with Ostermilk. We got into a routine of rising early so that we could climb the further 2,000 feet to the caves in relative cool. Our biologists would go into the new caves first, so as to collect their specimens in relatively undisturbed conditions. Most of the caves were deep sink-holes which meant that several of our home-made rope-ladders had to be lashed together. It was an acrobatic challenge for Jon and Malcolm, the surveyors, to record what we had found with measurements and drawings.

The children helped us to collect specimens to take back to the British Museum, cheerfully wringing the necks of the lizards until we demonstrated a more humane way – popping them into a jar of chloroform. Bat-catching was highly entertaining for spectators. Tim would be knee-deep in guano with Phil on his shoulders, poking a stick into roosting holes then merrily swooping with a butterfly net until they both over-balanced and ended up in the muck. What wasn’t quite so funny was when Phil injected formalin preservative into a dead bat and then accidentally injected himself with the same needle. I woke up one morning to find a scorpion had shared my sleeping-bag – he joined the bats and lizards in formalin.

It was my turn to stay on watch at our base camp while the others tramped off to the caves. There were the obligatory few spectators; shepherds who would spend all day just watching our antics, while their goats would forage for what little was on offer in the desert (thistles, presumably). I was deeply engrossed in Jane Austen’s ‘Emma’ (obviously taking my look-out responsibilities seriously), when I was surprised by the rapid return of the team. They had been dropping stones down a new-found hole and listening to them falling to incredible depths, when they heard the unmistakeable yowl of a big cat. They had rushed back to tackle up for a possible confrontation – petrol-soaked rags tied round a stick, a knife… and a camera – off they went again; huntsmen on a mission. I was left to contemplate how I would get home if they were all eaten. To my relief, they returned with stories of an empty cave, but a gnawed donkey’s leg was evidence of the cat’s domain.

Used to being rather picky with my food at home, in Iran I was grateful for a scrape of Shippam’s crab paste on a dried-out husk of naan bread and a few raisins for lunch, whilst enjoying an eye-scorching view of scrub-encrusted mountains stretching in all directions. Letters home show how much I craved corned-beef hash. We had been away for six weeks and even the occasional bar of melted chocolate with a hazelnut in every bite couldn’t raise any energy. We became accustomed to living with the dirt; not surprisingly we were constantly ill, but somehow a team spirit prevailed. We were a diverse bunch of characters: a couple of firebrands alongside three easy-going types, a sparky comedian and me. Apparently, my unwitting service to the community was in preventing the others from descending into savages.

It was time to move on. When we left Malayer, the villagers surprised and alarmed us by belligerently showering the Land Rover with stones. Our rear-guard, on foot, had to scramble aboard for a hasty getaway – we had outstayed our welcome.

We decided to spend our last week in Iran visiting a wet cave system that we had heard about. Ali Sadr was a few miles along the Kermanshah road from Hamadan. In this greener haven, there were grapes and figs and a well-kept village nearby. It was like a new lease of life; we hurried into our caving tackle and went below to enjoy the twinkling formations in the roof and to stare in awe at the enormous underground lake. Our surveyors had difficulty getting any help as the rest of us fiddled about with candles and camera equipment, conjuring up atmospheric shots. When we returned to camp, we were astonished to find half the village, unusually including women this time, seemingly fascinated by Steve, our geologist, calmly reading ‘Lord of the Rings’ in the shade of a tree.

Early the next day, armed with a bag overflowing with our filthy washing and some ‘Ola’ soap, I was directed to the qanat by a throng of women and children. The women generously took over my washing and were extremely thorough in their work, managing to get even the grubbiest items clean. I washed my hair and the children followed my example, but two of them ended up in tears, probably due to the ‘Ola’ in their eyes. A little girl called Tahira took a shine to me – she was surprised that I had no children of my own, whilst I felt I was little more than a child myself. While we waited for the washing to dry, two of the women proudly showed me their neat houses, with colourful rugs on the floors and pictures on the walls. Then we visited the shrine of a deceased relative, a room full of happy memorabilia.

My most frightening experience was night-watch duty in a border area known for thieves who would take everything, including the makeshift pillows of rolled up clothes, stuffed under unwary heads. A non-smoker, I chain-smoked for half an hour, eyes straining, head on a swivel, expecting every shadow to turn into a brigand. I was the first watch of the night and should have been able to guard the camp for longer, but I was a cringing coward and woke Malcolm, who was justifiably grumpy that he had only just nodded off. The weight of responsibility lifted, I burrowed into my sleeping-bag for a deep and untroubled sleep!

My perspective on life shifted on that trip. Our lives back home were cosseted; our parents had lived through the deprivations of war, but we were blithely unaware of hardship, we were clean and well-fed. We received the results of our degrees while we were in Iran, but those successes were insignificant compared to the daily struggles of a woman whose baby’s head was covered in sores and who was unlikely to receive treatment in the desert. The children in Iran had to grow up quickly to an uncertain future and more upheaval was on the horizon with the end of the Shah’s reign.