In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, how did Berkhamsted weather health crises in the past? Two articles in a previous Chronicle investigated food standards and health hazards in the town.[1] A worthy aim was “to prevent disease where it could be prevented, to save life where it could be saved, and to get rid of evils arising from neglect, filth, and other conditions which contaminated the air and the water”.[2] Applying preventative measures following the Public Health Act of 1848 appears to have been successful in the town except for child mortality which prompted a rise in birth rate, but contemporary memoirs show that this “never compensated emotionally for those who were lost”.[3] By the 1870s, the local Board of Guardians pronounced Berkhamsted “the healthiest place in England”, boasting a good proportion of natives in the upper age bracket.[4]

In 1832, Mr. Collier was appointed medical officer for Northchurch and it proved to be a busy year for him, due to the prevalence of cholera in the village. Money was raised to relieve distress and much of it was spent on improving sanitary conditions as it was observed that: “A great many drains and cesspools are in a very foul and unhealthy state.”[5]

By 1853, vaccinations were made compulsory, but no one was given the power to enforce it. The Registrar presented a favourable report on health in England in 1854, “Cholera has not prevailed to any extent, but the mortality of the town districts has slightly exceeded the average, and the diminution in mortality is found to be chiefly in the country districts”. He pointed out that “Small-pox… victims have been chiefly amongst the very lowest class of the population, and in almost every case vaccination has been entirely neglected, or improperly attended to.”[6]

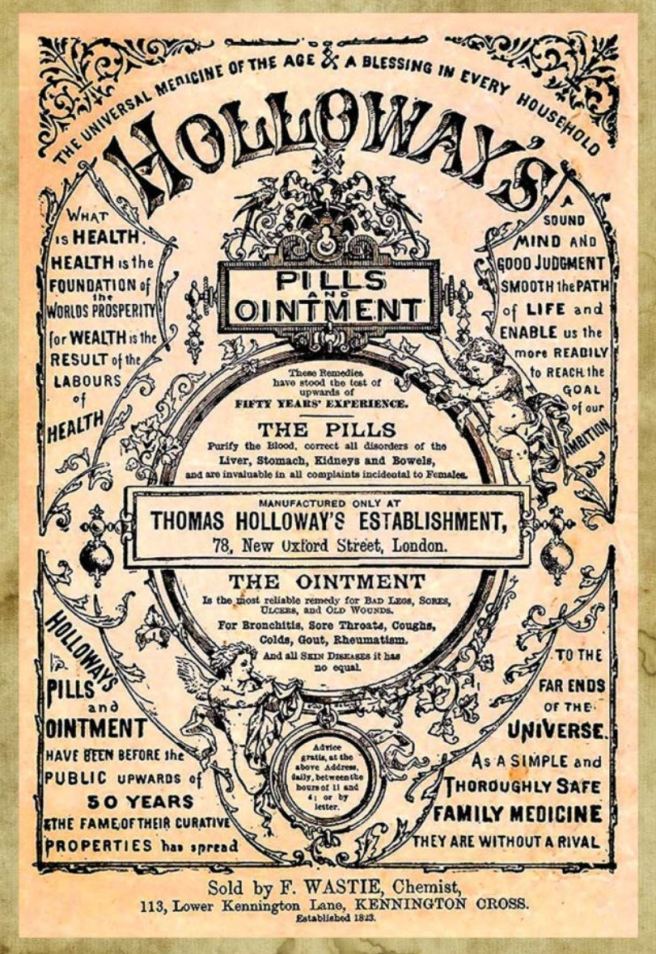

Real progress was made in combating disease when Pasteur’s germ theory was published in 1861. Five years later, John Snow furthered the cause when he successfully demonstrated that contaminated water carried cholera. At about the same time, sufferers were encouraged to try “quack medicines” (or if you prefer, “folk remedies”) such as Holloway’s Ointment or Allenby’s Carminative Red Mixture. Holloway’s acted “like magic” in the relief of diphtheria, bronchitis, sore throats, coughs and colds (secret ingredients being aloe, myrrh and saffron). Allenby’s was a safe and effective cure for diarrhoea and English cholera (with aromatic and vegetable properties, free of chalk).[7]

By 1870, “thanks to the beneficial operation of the Vaccination Act, we are glad to find the figures are becoming small by degrees and beautifully less”. Following the deaths of thousands in previous years, just 45 died of smallpox in England that year. Seven people had died of scarlet fever in Tring and one in Berkhamsted. There were just two deaths from diphtheria, but 51 of whooping cough in Hertfordshire, the epicentre for that outbreak being Rickmansworth.[9]

An enumerator for the 1871 census “nearly scratched from the top of his head the few hairs which still grace it” when confronted with hostility while distributing schedules. On returning to collect the form from one household, he “found a female nursing a child with a well-developed form of small-pox”. He quickly “made tracks”, rushed home, consigned the infectious schedules to the backyard for the night. They did not enter the house again without thorough fumigation and his family were forbidden to enter his study until he had transferred the information into his enumeration book. District Registrars were warned “he has threatened that he will, with one blow, reverse the perpendicular position of any one who asks him to again assist in taking the census!” [10]

Tring was a hub of anti-vaccinationists and Mr. Garnet Jones, relieving officer of Berkhamsted Union, had his work cut out in persuading them to have their children vaccinated. In presenting the case to the Board of Guardians, “several times expressions more warm than dignified, passed from the accused.”[11] Among the excuses given were: the child was dead, there was no child of that name in the household, the child was in a healthy state and they wished to keep it so, or they had not been served with a proper regular notice. They believed that vaccination did more harm than good, adding that the law that enforced it was cruel and unjust. Mr. Hadden replied: “Well it is the law, granted it is a cruel law, you are bound to obey it”. Chairman: “Make the order”. Henry Stevens had been summoned seven times. He had paid the penalty twice and he was defiant in his response: “They might go on and ruin him, which they could”. The bench thought it very creditable to Berkhamsted Union to have the law enforced and an order was made again.

In 1876, the Board of Guardians showed signs of fatigue in their quest, debating whether to ask the Local Government Board if it was necessary to repeat prosecutions after a parent has been fined for a non-vaccinated child. Three voted for it and nine against, so the motion was lost.[12] Objections to the enforcement of vaccination continued and by 1877, still “several persons had neglected to obey an order”.[13]

In 1878, “It has been the misfortune of Berkhampstead to have had imported into it a number of small-pox cases, while Tring, an anti-vaccination town, has escaped”.[14] Edward Simms Leigh, a wine merchant in London had sent his servant Clara Bridges home to Amersham after she had complained that she was bilious and had attempted suicide by cutting her throat. These symptoms were later assumed to be due to smallpox fever and she was admitted to the Union Workhouse. Berkhamsted’s Mr. Penny had defended Leigh but the Bench ruled that gross negligence had been shown and a fine of £3 was imposed, with £3 7s. costs (about £420 today).[15]

Arrangements were made for payment of compensation for the clothing of smallpox sufferers destroyed by the Medical Officer. Stations were set up in the area for children to be vaccinated, though objections were raised in Little Gaddesden, resulting in vaccination officers visiting parents’ homes.[16] The Berkhamsted School Attendance Committee chaired by F.J. Moore agreed that the Vaccination Register could be used to record children’s absence in school books, and “proceedings were authorized to be taken against a number of persons for having employed children”.[17]

In 1884, the all-causes mortality rate in the town was 120 per 1000 population.[18] Zymotic diseases (scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough) accounted for just five deaths from scarlet fever in Berkhamsted. There had been whooping cough in Wigginton, measles in Aldbury and one death from diphtheria in Long Marston. It was noted that Berkhamsted had “greatly benefited by the system of scavenging [rubbish collection] adopted, and the advantage of nuisance inspection is well seen here, with the result of staving off a large expenditure for a sewerage system”; also that the “desirability of closing schools during the early days of an epidemic is a fully-proven fact, and this should always be done”.[19]

The Berkhampstead Anti-Vaccination League protested against any enforcement of vaccination, citing fatalities and disasters from the procedure itself, people still dying after vaccination, unjust targeting of the poor, persecution of individuals whilst whole communities (such as Leicester) defied the law and yet suffered the fewest deaths per population in England.[20]

In 1895, the town crier posted an announcement: “The sale of distrained goods for non-compliance with the compulsory vaccination order will take place… in the Police Station-yard. It is hoped that the Guardians from Tring and Berkhampstead who have ordered the dirty work to be done will be present and bid up like men”. The auctioneer Mr J. North presided over a well-attended and good-natured crowd.[21]

Mr Engeldow, secretary of the local Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League in 1896, paid a fine and costs on behalf of a labourer named Bergen of Bell Lane Northchurch whom he brought home from St Alban’s gaol (where he had been sent because he had insufficient furniture to settle the claim) but his child, who was ill at the time, died.[22]

Debate was still raging about the efficacy of vaccination in the Board of Guardians later in 1896. Some argued that towns where most of the population was vaccinated still succumbed to the disease whereas others were grateful that their lives had been saved. There was much hilarity when it was reported that the President of the Anti-Vaccination League himself had been vaccinated.[23]

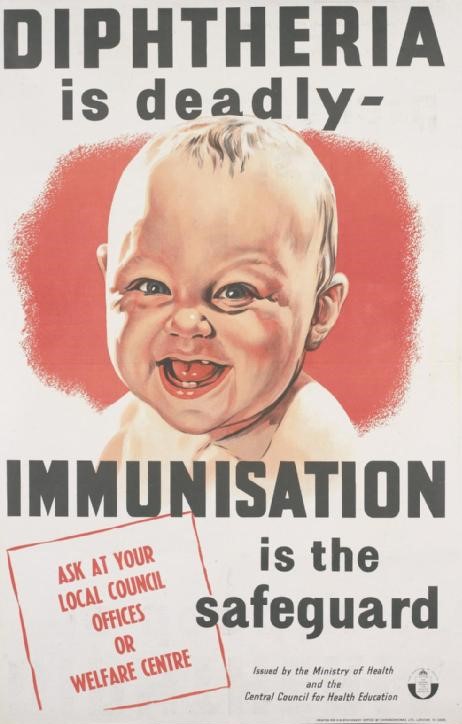

Les Mitchell remembered when the town was struck by diphtheria in 1936, affecting many school children. They were taken to an isolation hospital near to Aldbury in a small canvas-covered ambulance.[24] The hospital was built soon after 1872 and was so advanced in design that the plans were borrowed by several other sanitary authorities. At the turn of the century, during another wave of diphtheria, the fever cart was a much-dreaded sight. Children were taught to hold their breath as it went by. Some relief had come in 1898 when rubber tyres were fitted to it so that it made a less frightening clatter.[25]

Notwithstanding grim tales of Victorian life portrayed by Dickens an others, “the moment at which the prevalence of degenerative disease overtook that of infectious disease came during the Victorian era”; the nation rose from its sickbed after life expectancy in urban slums in the 1830s-1840s had been the lowest since the Black Death.[27]

[1] Rollitt, L., ‘Food standards in Berkhamsted’ and ‘Health Hazards in Victorian Berkhamsted’, Chronicle, v.XV, pp.27-31, 50-56

[2] Bucks Herald (Oct 1896)

[3] Crone, V., ‘Was Victorian Life Really So Grim?’, History Extra (Nov 2015)

[4] Bucks Herald (Feb 1876)

[5] Birtchnell, P., ‘Fighting an Epidemic’, Berkhamsted Review (Nov 1957)

[6] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (12 Aug 1854)

[7] Herts Advertiser (21 Dec 1867 & 19 Sep 1868)

[8] Available as A4 print from Andromeda Print Emporium on Amazon

[9] Herts Advertiser (21 May 1870)

[10] Herts Advertiser (27 May 1871)

[11] Hemel Hempstead Gazette and West Herts Advertiser (20 Jun 1874)

[12] Hemel Hempstead Gazette and West Herts Advertiser (26 Feb 1876)

[13] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (24 Mar 1877)

[14] Bucks Herald (Feb 1878)

[15] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (23 Mar 1878)

[16] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (10 Sep 1881)

[17] Uxbridge & W. Drayton Gazette (2 Nov 1878)

[18] This compares to 9.4 UK deaths per 1000 currently (website accessed Jul 2020)

[19] Herts Advertiser (10 May 1884)

[20] Bucks Herald (Jul 1894)

[21] Bucks Herald (Nov 1895)

[22] Bucks Herald (Feb 1896)

[23] Bucks Herald (May 1896)

[24] Read more memoirs here: Mitchell, L., ‘It was but yesterday’

[25] Cook, J., Berkhamsted Review (Oct 2000)

[26] IWM, Artwork in Public Domain, Ref: PST 14182

[27] Crone, Victorian Life, quoting figures from the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure