Why is Humphry Repton worthy of attention when Lancelot “Capability” Brown is still recognised as the most famous landscape designer in English history? Repton’s significance develops from following in Brown’s footsteps, then setting himself up as his successor, promoting and codifying the art of landscape gardening and satisfying aristocratic estate owners with his own unique methods and designs. He improved on Brown’s reach by scaling down and introducing practical solutions for the less wealthy who wished to emulate the elite, thus setting the scene for the “gardenesque” style. While he faced many challenges, we can appreciate Repton’s skills and innovation and examine the impact he had on his contemporaries. Indeed, his influence extends to the present day and his garden designs can still be admired locally at Ashridge.

To appreciate Repton’s contribution, it is useful to look at thechallenges he faced; some beyond his control, others due to personal attributes and misfortune. Perhaps it was unwise to profess himself Brown’s successor, because while he rode the crest of a wave of his popularity, he also suffered from criticism of his style, particularly from “picturesque” theorists Uvedale Price and Richard Payne Knight.[1] Price wrote a light-hearted account of two connoisseurs of the picturesque enthusing about “a hovel under a gnarled oak, a rude cottage, thorns, heath, gypsies in the shadows, pollard oaks and a rusty donkey”; a third chap (referring to Repton), eager to learn, thinks “picturesque objects are plain ugly”.[2] It appears Repton was able to parry unkind remarks with wit, but he was apparently bitter about the public ridicule he endured.[3] His personal sensitivity and snobbishness, the need to ingratiate himself with the aristocracy, along with previous failings in business, conspired against him.[4]

Without the practical capabilities of Brown, Repton often left the job of implementation to others; this meant that some of his grand designs were never realized. His less-than gracious response to landowners who failed to action his ideas came across as arrogance. The Napoleonic Wars brought rising taxes and fewer commissions, but his ingrained fear of poverty drove him to accept work from the despised nouveaux riches.[5] He emulated Brown’s peripatetic life, travelling far and wide to engage new clients, referring to a post-chaise as his “writing desk”; it was a shock when a carriage accident in 1811 confined him to a bath chair.[6]

If Repton had a curriculum vitae it would have contained a range of enviable skills, foremost as an accomplished watercolourist. He was able to bring an artist’s eye to the landscape with placement of trees, re-routing driveways to frame his clients’ properties and obscuring boundaries to embrace the surrounding countryside.[7] In his early projects, his style closely followed his mentor, bringing to mind Richard Owen Cambridge’s (unfulfilled) hope to die before Brown so he could “see heaven before it was ‘improved’”.[8]

Unlike Brown, Repton was skilled at sharing his knowledge via authorship of theoretical books, including his Sketches and Hints; in which he sets out eighteen principles which can be summarized as enhancing and extending natural beauties, disguising defects and accommodating domestic utilities.[9]

Was he, as Richardson writes, “like Brown, an extremely canny businessman”?[10] There is no disputing Brown’s business acumen and his natural ease with his clients, but Repton had to fall back on his tenacity and eagerness to please.[11] He excelled over Brown with his flexibility – he took a realistic approach as self-branded “landscape gardener” with the ability to design grand estates as well as more modest holdings.

A quick learner, Repton’s trade card shows him operating a theodolite, a skill apparently picked up from engineers who were busy constructing canals at the time.[12] Like Brown, he was concerned with architecture of the houses as well as their settings and worked frequently with architects including his son.

Repton’s trade card, 1788-1789[13]

Repton’s greatest innovation was the development of his red leather-bound books as marketing tools, granting him access to the elite and helping them visualize the potential of their properties. Repton loved performance and was perhaps inspired by magic lantern “slides” and “reveals”; his paintings incorporated cut-out overlays to show the before and after effects of his improvements “to entertain and delight his clients, as well as sell his services”.[14]

Another innovation was the introduction of sounds and movement into his landscapes. Biographer John Phibbs wrote that Repton liked to elicit an emotional response; sudden vistas, sounds from cascades or the “burst” after emerging from a dark wood.[15] Repton brought back some formality near the house by building terraces and planting flower gardens, thus setting the stage for the “gardenesque” style that developed during the nineteenth century.[16]

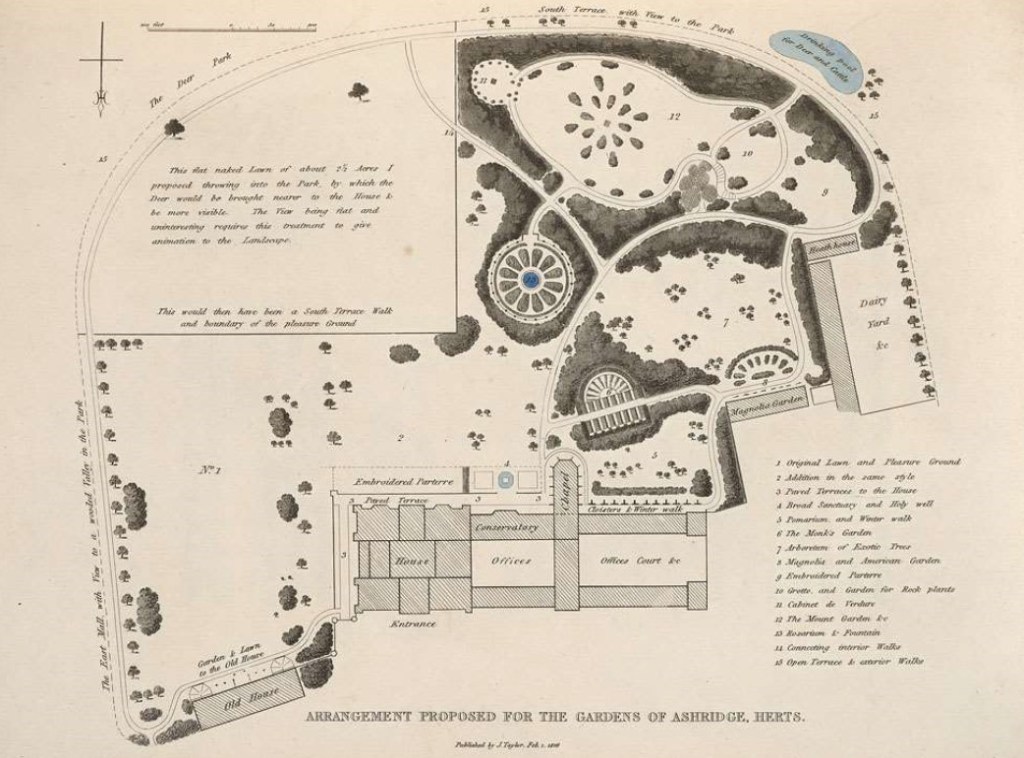

In 1813, Repton presented a plan for Ashridge of 15 different gardens to the 7th Earl of Bridgewater which he described as a “Modern Pleasure Ground”. The gardens included an arboretum, a grotto and a rock garden, rosarium, monk’s garden and a flower stove referred to as an “embroidered parterre”, reminiscent of Woburn.[17]

Many of the features proposed in Repton’s red book for Ashridge in 1813 “became classic elements of Victorian garden design”.[18] In 1816, Repton wrote flatteringly of the Earl: “… knowing the wish of the noble Proprietor to direct every part of the improvements both in the house and grounds, I could not but feel highly gratified on being desired to give my opinion concerning the manner of adapting the ground near the house to the magnificence and importance of the place and its possessor”.[19]

What impact did Repton have on his contemporaries? Richard Payne Knight criticized Repton’s red book for Tatton Park (1791) as insufficiently picturesque, only showing the owner’s “wealth in land, and poverty in mind”.[21]

Jane Austen knew of Repton because he was commissioned by her mother’s family for Stoneleigh Abbey.[22] She had given Edward Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility opinions in opposition to Uvedale Price’s “rugged paraphernalia” of the picturesque.[23] He preferred “a snug farmhouse rather than a watch-tower and… happy villagers [rather than] banditti”.[24] Many land owners tried to emulate picturesque artists’ grottos, rustic bridges and Gothic arches; most “turned back… to the maligned Repton”.[25]

Repton’s greatest legacy was his books, which have influenced garden design both at home and abroad. The Woburn Abbey red book represents the most elaborate and intact Repton landscape, produced in 1804, and as a measure of his continuing influence, it continues to be used to direct ongoing restoration projects. His ideas were often challenged and he worried about his reputation, but “his influence on English landscape gardening has proved more powerful than that of any of his predecessors, rivals, or successors”.[26] Opinion turned towards stability following the French revolution; it was time for the wilds of nature to be tamed and Repton was the man for the job, a realist who believed convenience was as important as beauty. In conclusion,Humphry Repton succeeded Brown and received both accolades and opprobrium as a result. Following Brown’s sometimes rather bland and bleak style, Repton satisfied his clients’ need for stability and domestic convenience, adding features near the house (flowers, terraces) to soften the transition to the garden. He also liked to include movement of some sort to his more homely scenes, even if just smoke from a cottage chimney. Perhaps he lacked the finesse required to secure commissions from the elite, but unlike Brown, he wrote influential books about his style and numerous bicentenary events in 2018 showed that his work has lasting appeal.

[1] Willis, P., ‘Repton, Humphry (1752-1818)’ in Crowcroft, E. & Cannon, J. (Eds.), The Oxford Companion to British History (2 ed.) (2015)

[2] Batey, M., ‘The Picturesque: An Overview’, Garden History, Vol. 22, No. 2, The Picturesque (Winter, 1994), p. 123

[3] Daniels, S., ‘Repton, Humphry (1752-1818)’, ODNB (2012)

[4] Mayer, L., Humphry Repton (2014), p.15

[5] Daniels, Repton

[6] Uglow, J, A Little History of British Gardening (2005), Chap.15

[7] University of Oxford and contributors, ‘Unit 7: Humphry Repton and Regency gardening’, English Landscape Gardens: 1650 to the Present Day (accessed Nov 2021), Chap.7.2

[8] The Twickenham Museum, Richard Own Cambridge (1717-1802), http://www.twickenham-museum.org.uk/detail.php?aid=32&ctid=1&cid=15 (accessed Dec 2021)

[9] Repton, H., ‘The Art of Landscape Gardening including his Sketches and Hints…’, Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/61363#page/11/mode/1up (accessed Nov 2021)

[10] Richardson, T., The Arcadian Friends: Inventing the English Landscape Garden (2007), Chap.26

[11] Mayer, Repton, p.18

[12] Gardens Trust, Repton and his Business (2018),

https://thegardenstrust.blog/2018/01/06/repton-and-his-business/ (accessed Dec 2021)

[13] Ibid.

[14] Garden Museum, Humphry Repton: A Generous Deceit (2018)

https://gardenmuseum.org.uk/film-library/humphry-repton-a-generous-deceit/ (accessed Nov 2021)

[15] Phibbs, J., biographer of Repton and Brown, quoted in Richardson, T., ‘A beginner’s guide to Humphry Repton: landscape genius’, Telegraph (Mar 2018)

[16] Loudon, J.C., Repton’s Landscape Garden (1840), Introd.8 (from OED)

[17] Thompson, M., ‘Humphry Repton and the Development of the Flower Garden’, Garden History, 47, suppl.1, p.68

[18] Garden Visit, Ashridge Garden, https://www.gardenvisit.com/gardens/ashridge_garden (accessed Dec 2021)

[19] Repton, H., “Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening” (1816)

[20] Ibid.

[21] Payne Knight, R., The Landscape: A Didactic Poem (1794), pp.11-12

[22] Richardson, T., ‘A beginner’s guide to Humphry Repton: landscape genius’, Telegraph (Mar 2018)

[23] Batey, Picturesque

[24] Austen, J., Sense and Sensibility (1811), chap.18

[25] Uglow, Little History

[26] Daniels, Repton