An investigation of a family mansion in the neighbourhood of Great Gaddesden, and especially highlighting a dispute about an access road, revealed divided loyalties, but also the importance (particularly to older inhabitants) of “tradition, community and custom [which] historically provided a sense of permanence, independence and security”.[1]

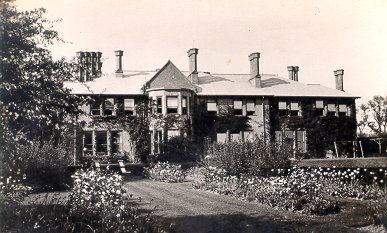

Gaddesden Hoo was sandwiched between the estate of the Countess of Bridgewater and land belonging to the Halsey family of Gaddesden Place. We get an appreciation of the splendour of The Hoo from details of a sale in 1834, when Henry Greene, a previous owner, died.

The excellent household furniture, in four-post and other bedsteads and furniture, capital feather beds and bedding, mahogany and painted dressing tables and glasses, chest of drawers, commodes, Brussells and Kidderminster carpeting ; mahogany dining tables and claw, and other tables ; mahogany chairs and sofas, eight-day clock, secretaire and bookcase ; books, linen, and china ; kitchen requisites, brewing utensils, sweet iron-bound hogshead, and other casks, beer stands, and various other effects.[3]

The sale of farming stock at the time reveals that the estate was a going concern:

… comprising four useful cart horses, black pony, five in-calf cows, 145 Southdown wether sheep, three sows, 24 store pigs, poultry, &c. ; narrow-wheel wagon, four carts, three land rollers, donkey cart, ploughs, harrows, 23 dozen hurdles, cart and plough harness, barn tackle, cow cribs, sheep troughs and racks, quantity of wheelers’ stuff, &c. ; also 50 loads of upland well-got new and old meadow hay, hovel of wheat, and bay of ditto off thirty-two acres, two ricks of barley off sixteen acres, ricks of oats, and stump of ditto off twenty-five acres, and other valuable effects.[4]

In 1836, the “exclusive right of shooting over nearly 400 acres of land, nearly 30 acres being wood land” was advertised, along with letting part of the mansion, consisting of:

… a dining and drawing room, four good bed rooms, and two servants’ rooms ; a good kitchen, and other convenient offices ; a four-stall stable, coach and wood houses, with a good garden.[5]

The Hoo was again for sale by auction in 1843, with tenants Messrs. Gostelow and Hoare providing particulars:

… a capital and delightfully situate family mansion, with stabling, coach-house, walled garden, pleasure grounds, and all the various appendages for a country establishment ; surrounded by a rich park, studded with handsome timber; also, two valuable and picturesque farms adjoining [Hoo and Ledgemore] … with three complete homesteads and two labourer’s cottages… offering a most desirable residence for any family of distinction, and particularly suited for a wealthy merchant or banker, from its constant and easy connexion with the Metropolis.

By 1845, George Proctor (also spelt Procter), the new proprietor, was advertising: “A large fall of capital oak, ash, elm and beech timber trees, with their lop, top, and bark… standing marked and numbered upon the Hoo Estate”.[6] Timber was another form of income for country estates, particularly in the Chilterns where turned wood products were a regional speciality.

George was born in 1789 at Heath and Reach, the second son of John and Ann Procter. Their eldest son John had died in infancy and 12 more sons and daughters were born in Leighton Buzzard. George was a snuff manufacturer, later investing in land and houses. He died on 30 Nov 1861. One of his brothers, Henry, was a master butcher living in Islington with his wife Elizabeth née Ivory. On the death of their younger brother Percy on 1 Feb 1884, it was reported that he was the last member of a family of six brothers and three sisters, all unmarried, who for many years resided in Leighton. Three sisters had died within a remarkably short space of time: Mary Ann on 9 Dec 1881, Emma on 4 Feb 1882 and Elizabeth on 10 Feb 1882. He left one brother surviving, Thomas Procter, of the Gaddesden Hoo, Hemel Hempstead, who died on 27 Dec 1886 and was buried at Great Gaddesden church.

In 1887, The Hoo and Ledgemore farms along with “10 powerful cart horses”, cattle, sheep and pigs were sold by direction of the Executors of the late Thomas Procter, Esq.[7]

Later that year, peace was disrupted in the community when a dispute began over whether the road passing The Hoo was public or private. The first charge was brought by a surveyor of highways, George Young of Water End, who accused Thomas’ son Joseph Proctor of the Hoo with wilfully obstructing the highway at Great Gaddesden. The case aroused much public interest, with some forty witnesses appearing for the prosecution.[8] An ordnance map “showed the road in question, but a tithe map… did not give it that form”. This online map shows The Hoo and surrounding farms, many of which retain their old names.

(Red dotted lines with diamond shapes denote national trails / public access)

The prosecuting counsel listed ownership of The Hoo for several years, starting with ‘Squire Green and naming his successors as tenants, ending with Mr. Gostelow. In 1844, “Mr. George Proctor purchased the estate, which came to Mr. Thomas Proctor, who died in 1886”. Apparently in all this time, the gate of the road had not been locked to the public, but “during Mr. [Thomas] Proctor’s illness, a request was made that carts might not be driven along the road under the windows of the house”.

Following an enquiry as to why this (allegedly public) road had been stopped, a vestry meeting was held and after due notice, the gate was forcibly opened. The road was obstructed again, this time by “placing stones, timber, and a deep trench across it”. Another vestry and a parish poll found the majority in favour of the road being public. Mr Young said that he had known the road for fifty years, and it was always a public highway for any vehicles. A succession of old men trooped into the court room to contend that the road had been public in their living memory though one said that (not unreasonably) “the late Mr. Proctor had asked him to shut the swing gate that the cattle might not get out of the park”. Several of the witnesses “were so feeble that they had to be accommodated with a seat, and hardly any of them could do more than make their mark to their depositions.” After 26 witnesses had given evidence in the same vein, the prosecution counsel decided not to call the remaining 29 who had the same story to tell.

At the next court sitting, the case began for the defence with Joseph Chennells, farmer of Edlesborough, aged 82, whose family had occupied Church Farm in Great Gaddesden for 160 years; he had also worked at Marsh Farm, less than a mile from The Hoo.

He remembered from 1831, when as a boy he went for medicine to Market-street, and returned with another boy who had medicine for Miss Green, and the boy found the gate in the Hoo-lane in question locked, and had to go back.[10] He as surveyor never repaired the lane, which was always considered to be a private road. ‘Squire Green, the previous owner of The Hoo, gave permission to witness’s father to use the lane, but it was overgrown with boughs and almost impassable.

Other witnesses spoke of the lane being private, including Ann Woodman, of Tring, governess at The Hoo from 1864 to 1874. The case continued into another day in a cramped committee room, with Thomas Proctor’s widow, four of her sons and four daughters in attendance.

Mr. Joseph Proctor spoke of being at home after leaving Berkhampstead School, and also in holiday time, and gave many instances of his father refusing the use of the lane or road to the public. He did not, however, object to neighbours driving by. Mr. Hugh Proctor, farmer at Field’s End and neighbourhood of 850 acres, also auctioneer and surveyor at Berkhampstead, eldest son of Mr. Thomas Proctor, spoke of the whole of his experience being in favour of the road being private.

Several members of the Proctor family and others gave confirmatory evidence. Having cleared the room for consultation of the Bench, the case was dismissed with both parties paying their own costs.

That was not the end of the story. A couple of months later, there was a “lively scene” following the actions of some courageous farmers mending a large hole in the road that had been filled with black water, preventing people passing that way. Four policemen were called to the scene where “In the course of the proceedings one of the gentlemen lost his hat and stick, which were buried in the hole.”[11]

In the subsequent court case, Mr. Henry Taylor of the Marsh Farm, Great Gaddesden, was summoned for assaulting Mr. Hugh Proctor and in a cross-summons, Mr. Procter was charged with assaulting Mr. Taylor at the same time and place. The Bench “regretted that there should be so much ill-feeling relating to a case… and Mr. Taylor and Mr. Procter would be bound over to keep the peace for six months, and each would have to pay his own costs.”[12]

The following month, not to be outdone, Mr. H. Taylor of Marsh Farm gave notice to Mr. Hugh Procter that he would exercise his right to pass along the road through the Park as he and his predecessors had done for years without hindrance. Mr. Procter replied that Mr. Taylor would be committing an illegal act, and forbade him to do so. Mr. Taylor, after filling in the deep and wide hole that had been cut into the roadway, sent a cart laden with bricks over the forbidden road to Marsh Farm. There was no attempt at interference from the Procter family.[13]

The dispute rumbled on into 1889, with another court case brought by 67-year-old Henry Taylor of Studham Hall Farm versus the trustees of the late Thomas Proctor, of The Hoo. Messrs. Hugh, Harold, Joseph, and John, and the Misses Proctor, sons and daughters of Thomas, were in attendance.[14]

Referring to a model of The Hoo with the road and adjacent farms, and several maps of the district, the case was opened with the important question as to whether the public had a right of way for horses and carts along the road. Witnesses would be called to prove that the road had been repaired with Mr. T. Proctor’s assent (indicating its status as a public road) and many who had used the road unimpeded. Henry Taylor testified that he had lived at Hatches Farm and went to school in Great Gaddesden via Hoo-lane; he had driven along the road for years, was never stopped and had never known the gates to be locked.

His father built some cottages at Gaddesden-row, and the stuff was carted from Berkhamsted along the road by Potton End and Water End. He had taken stock and corn that way many times, and no one ever attempted to stop him.

After his father’s death in 1871, Henry Taylor inherited Hatches Farm and other land, about 600 acres. His brother (Thomas Taylor) occupied Marsh Farm.

He had been on speaking terms with the late Mr. Proctor, but was not particularly friendly. His father and he had taken stones to repair the road for the parish… Hatches Farm was badly off for water, and they fetched water from the Marsh Farm down the Hoo-lane.

George Young, of Water End, had used the lane many times in discharge of his duties as registrar of births and deaths. He had never been stopped until Jul 1887 when he found the gate locked on returning from Gaddesden-row. He called at The Hoo in his capacity as surveyor to enquire why the road was stopped as he thought it would cause unpleasantness and ill-feeling in the parish. They said they did not like the manure carts passing there. Young had repaired the road many times and a drain had been installed and paid for by the parish. Hedges had been cut and snow removed from the lane.

Along with other witnesses who viewed the road as public were Joseph Smith, 60, of Berkhamsted, in the employ of Locke and Smith’s and William Tarsey, 66, who said he had fetched timber unhindered for 30 years from Sir John Sebright’s ground for Mr. Read in Berkhamsted.

Continuing the case at the Kings Arms in Berkhamsted, David Potton, 59, of Ballingdon Bottom, who had worked at The Hoo from 1844 for three years, recollected a conversation between Mr. (George) Procter and a gentleman when he was out with them marking timber.

The gentleman inquired if that was a private road, and Mr. Procter replied, “Oh, no ; or I should have had to give a lot more money for it.” The gentleman said, “Can’t you get it made a private road?” Mr. Procter said, “No, we may not make any disturbance ; let it be as it has been.”

As part of his evidence, Potton revealed the extent of damage caused by the dispute. His own son Joseph had set fire to Ledgemoor (Ledgmore) Farm in May 1888; lives were saved only by the vigilance of a little girl who lived there. Potton had held a grudge against Joseph Procter who had dismissed him from his employ. David Potton did not know if Joseph was one of the ringleaders in the latest disturbances. The gate to The Hoo had been smashed up, the front door tarred, and a thrashing machine drawn by.

Thomas Rolph, 50, said his family had lived at Elm Farm for four or five hundred years. He had visited at the Hoo, and from 1851 to 1861 used to shoot there. Sir Thomas Procter had wanted to stop the two ends of Hoo-lane and put a gate to prevent traffic going that way, while Mr. George Procter objected because the road was a right-of-way for Studham people to Flamstead, as the road by the park was for Great Gaddesden people to Gaddesden-row. On another occasion Mr. Procter said about some carts passing the Hoo, “They are cutting this road all to pieces.” Mr. G. Procter said “Tom, my dear boy, you know I can’t help it.”

In support of the Procters’ case, that Hoo-lane was a private road, Joseph Chennells, 83, had been a tenant at Marsh Farm from 1831 to 1840. He maintained that the road from Ledgemoor gate to the Hoo was never used and there was no road from Hatches Farm to the Hoo – he said it was green baulk with no stones on it, all briars and bushes when he was a boy.

He used to go to his uncle’s at Hatches, and no one could get up the lane, but there was a path by the side. It was never considered to be a public road in his younger days.

When he was appointed surveyor, he was told that ‘Squire Halsey’s, The Hoo, and Mr. Bassil’s were all private roads. Timber cut on Earl Brownlow’s estate was carted through a field, because Thomas Procter would not allow it to go down his private road. The Hoo-road only led to the Hoo house in his time. Many more witnesses testified that the road was private.

The final discussion on the matter took place in Aug 1889, but the decision, to be written up by the arbitrator, Mr. R. Vaughan Williams (uncle of the English composer), would not be available for some weeks. The Hoo had been let for some time since the death of Thomas Procter, his wife and family having moved to the Red House in Berkhamsted.[15]

In pondering the question of tradition, community and custom in this case, it was plain from the court-room dialogue that there was high regard and fond memories of old ‘Squire Green of Gaddesden Hoo. His successor George Proctor also took a conciliatory approach to his neighbours. It appears that more effort was made to safeguard the privacy of the access road to The Hoo when George’s brother Thomas Proctor took ownership, perhaps even more doggedly by his sons following the firing of Ledgemore Farm. This was still a period when harsh punishments were meted out for trivial cases (to our eyes), such as cutting furze on the common or scrumping. Judges were keen to protect the property of the higher classes (to which they belonged). Who won the case? The arbitrator made his award in favour of the defendant, the Trustees of Thomas Proctor, with costs.[16]

[1] Young, T.E., Popular attitudes towards rural customs and rights in late nineteenth and early twentieth century England (Sep 2008), p.42

[2] British Listed Buildings, The Hoo, Great Gaddesden (listed in 1967), http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-157885-the-hoo-great-gaddesden-hertfordshire/photos#.WEaeyOaLQ2x (accessed Dec 2016)

[3] County Chronicle, Surrey Herald and Weekly Advertiser for Kent (09 Dec 1834)

[4] County Chronicle (14 October 1834)

[5] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (23 Aug & 30 Aug 1836)

[6] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (22 Feb 1845)

[7] Bucks Herald (8 Oct 1887)

[8] Bucks Herald (24 Dec and 31 Dec 1887) reported the first court case.

[9] Gaddesden Hoo, http://www.streetmap.co.uk/ (accessed Dec 2016)

[10] Markyate was called Markgate street or Market-street

[11] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (18 Feb 1888) details of renewed dispute.

[12] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (17 Mar 1888) reports a second court case.

[13] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (21 Apr 1888)

[14] Bucks Herald (17 Aug and 24 Aug 1889) reports a third court case.

[15] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (31 Aug 1889)

[16] Bucks Herald (14 Sep 1889)