Maintaining health in Berkhamsted during the Victorian period meant attending to the water supply and sewerage system, and dealing with industrial effluents, malodorous animals and dung-heaps. Luckily, Dr. Saunders, the local health officer, was a keen advocate of cleanliness, “the alpha and omega of hygiene”:

We can lower the present amount of illness if we choose… by purity of water, purity of air, and purity of the soil; in one word, cleanliness. Pure water is placed first in importance. Few think or care what is the character of the fluid they drink. Many an open drain, or even a cesspool, is in close proximity to the well, and thus the water, by filtrating through the soil, becomes a poison.[1]

The Great Berkhamsted Waterworks Company in Berkhamsted High Street was set up in 1864. A high-level reservoir at Kingshill was joined later by a low-level reservoir in Green Lane. (The water tower at Shootersway was officially opened in 1935).[2]

On Friday morning last, according to announcement, these works were thrown open, much to the rejoicing of the inhabitants. At the works there are two bath rooms, one for ladies and one for gentlemen, each subdivided into four compartments. The internal arrangements are excellent. The engine was kept going all day. The washing apparatus attracted particular attention of the ladies, to whom the notion of washing by steam afforded astonishment and amusement. The building, which is close to the Town Hall, was very tastefully decorated.[3]

Dr. Saunders also believed that consumption (tuberculosis) could be mitigated by good drainage and ventilation. The 1855 Nuisance Removal Act (which stated that overcrowded housing was illegal) was enforced to deal with the latter. For instance, unhealthy conditions at the Red Lion Yard came to the attention of the sanitary authority in 1886, and orders were made against several residents to abate overcrowding.[4]

Part of the town’s drainage problem had been addressed by accident with the arrival of the canal in Berkhamsted by the turn of the 19th century. An unexpected side-effect of digging the channel was that the water-table was lowered, thus saving the town from the disease-laden effects of the overflow from the River Bulbourne. Nevertheless, there followed several years in which local sanitary authorities battled with the “Black Ditch” and “Muggle Pit”. In 1874:

The present great nuisance might be abated by carrying a drain from Mr. Lane’s nurseries along the black ditch below the Gas Works, and then through the Grammar School Lane into the Castle-street drain… separating the sewage from rain drainage. This would purify the black ditch and remove the Muggle Pit nuisance [in Water Lane] without interfering with the miller’s water, and if the town is to be thoroughly drained afterwards this position would form part of the general scheme, and not be money thrown away.[5]

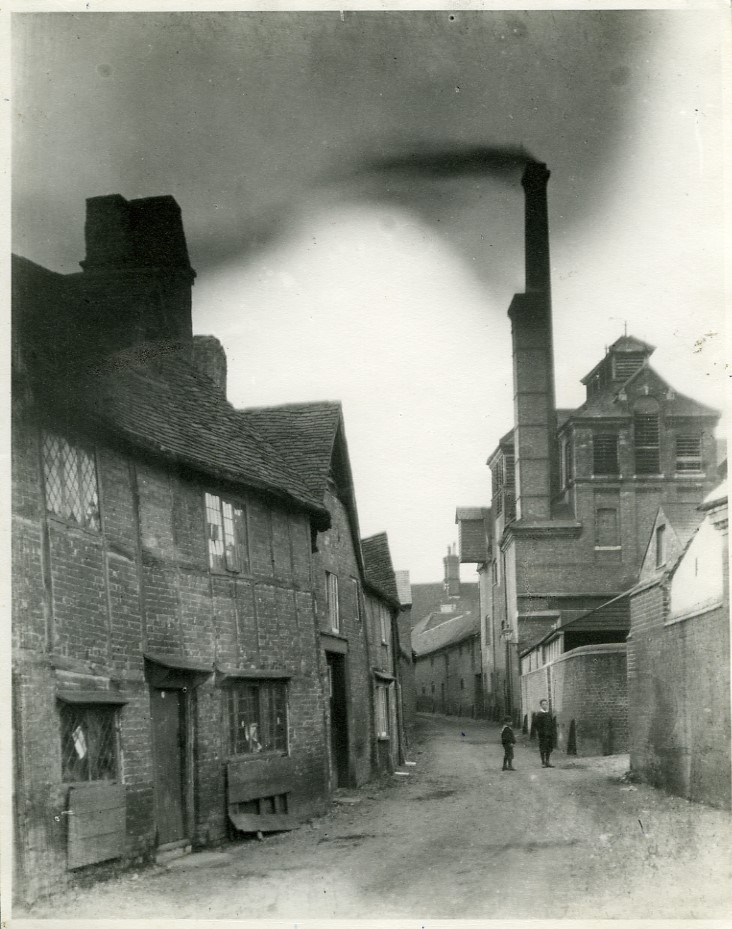

The muggle pit was in Water Lane, with an offensive smell caused by refuse from Locke & Smith Brewery

We learn of the location of the Black Ditch the following year, when Col. Smith-Dorrien accompanied Mr. Lane to examine it, beginning from St. John’s Lane and ending at a position opposite the Town Hall. Col. Smith-Dorrien reported that it seemed to contain nothing worse than soap suds. Mr. Hadden disputed this conclusion, saying that the whole of the sewage from the town, and much besides, was sent into that ditch. Rather belatedly, reporters were advised that they should not give the ditch a worse name than the “Back Ditch” which was what is always used to be called. Referring to the “Black Ditch” and “Muggle Pit” had caused some hilarity in local meetings![6]

The medical officer Dr. Saunders expressed his astonishment that the old privy and cesspool known as the town “Muggle Pit” was still in use when an earth or ash closet could be adopted:

Berkhampstead has waterworks, but advantage is not taken as much as it might be of obtaining pure water by this means. The wells in the town are in great numbers polluted by sewage, and a more fruitful source of disease diffusion it is difficult to conceive. The temptation to get water from the canal… too strong to be resisted… disastrously shown in the fatal cases of fever I reported due to this cause.[7]

In Sep-Oct 1875, the Sanitary Authority “were at their wits end what to do with the celebrated Muggle Pit, and the discharge therefrom”. One option was to fill up the pit and swim the drainage into the river, but that would just “aggravate the evil”. Other options were to cover it over, construct a brick tank to use instead, or carry sewage from Water Lane to Castle Street (it was unclear what would happen to it there).

At one meeting, Mr. Randall said when he went to market he was met with the inquiry, “Well, Randall, have you got out of the Muggle Pit yet?” which was met with laughter. The Muggle Pit had been cleaned out at a cost of £1 5s.[8]

In 1876, the Clerk laid before the [Rural Sanitary] Authority a resolution of the Parochial Committee of Berkhampstead and Northchurch:

“That a cesspool be formed in accordance with the plan now submitted by the Inspector, to receive the solid sewage flowing down Water-lane and Wilderness, with an outfall into the river,” and the Inspector produced a specification of the works and an approximate estimate of the cost. It was ordered that the same be approved and submitted to competition by the Committee.[9]

This option appears to have been implemented, because the Muggle Pit closed in 1880. However, the problem had not gone away because by 1888, a letter from the Rev. T.C. Fry complained of “a nuisance arising from the effluvia of the river caused by the deposit of sewage in the river from the town of Berkhampstead”. With the duties of the Rural Sanitary Authority about to be transferred to the District Council:

… it was not deemed expedient for the Authority to embark in any scheme for dealing with the sewage of the town which might not be adopted or carried out by their successors… [but in the meantime] special duties and powers [were invested] for the purpose of taking all measures necessary… for the flushing and cleansing the sewers and the river, and removing the noxious deposits.[10]

Mains drainage was finally supplied at the end of the 19th century, when the outgoing Rural District Council and the new Berkhamsted Urban District Council installed effective sewerage in 1898-9.[11]

An even more serious annoyance than the Muggle Pit or the Black Ditch apparently, Rev. E. Bartrum (1833-1905), schoolmaster at Berkhamsted School, complained “of a nuisance… from the foul and offensive effluvia from the Gas Works in Great Berkhampstead”. It was built in 1849 at the junction of Water Lane with the Wilderness to provide street lighting for the town.[12] The Rev. stated that the stench from the Gas Works was so bad that persons in both the houses under his charge were prevented from sleeping. The School Governors were contemplating making an extensive addition to the buildings close to the Gas Works, but, in his opinion, they would be almost uninhabitable unless the Directors of the Gas Company were compelled to do their duty, and abate the nuisance attaching to their works.”[13]

In a report in 1891, which also gives some insight into conditions in the Wilderness, Berkhampstead Gas Company was charged with committing a nuisance from the emission of offensive effluvia, injurious to the health of some of the inhabitants of Berkhampstead:

Dr. Fry (Head Master of the Grammar School) … had experienced bad smells for the last four years – a horrid stench of a sulphurous nature, which got into his house day and night at intervals. Mr. Muir… had erected a coach house, residence for his coachman, and a stable, near the Gas Works. The smell did not, he believed, come from privies and heaps of refuse in the Wilderness. The Gas Company authorities… undertook… to do their best to prevent any recurrence of any cause of complaint. The case was adjourned.[14]

In 1904, Dr. Fry said that Berkhamsted Grammar School had suffered much annoyance from the gas works and needed its existing site at the junction of Water Lane and the Wilderness to extend the school grounds. He believed there would be little nuisance when the gas works were re-built on modern principles, at Gossom’s End east of Billet Lane.[15]

Posing a more noisome threat to health on the outskirts of the town in 1868, the inspector of nuisances was guided to Cross Oak by the strong suffocating smell of putrid matter caused by a very large heap of thirty tons of dead hogs with two dead dogs on top, just sixty yards from the road. Mr. Wilmott, patent manure manufacturer, was charged with causing a nuisance injurious to the health of the inhabitants of the neighbourhood. Close by were some cottages and a house occupied by Mr. Keyser and Mr. Bovingdon, whose families and staff were badly affected by the smell. Costs and a fine were levied on Mr. Willmott, but he said that he would appeal against the decision.[16]

In 1889, the inspector said that following complaints he had received he visited Bartlett Ratcliffe’s baker’s premises and found nine pigs there, dirty and a nuisance. He had previously given the defendant notice in writing that the pigs were complained of by the neighbours, but fourteen days afterwards he found them as bad as before. The defendant was convicted and fined £2, including costs, or fourteen days.[17]

How successful were these health measures? Berkhamsted certainly appears to have been a popular place to settle in the Victorian era. By the 1830s, baptisms outnumbered burials (925 and 735 respectively) with a population of 3,525 in 1831; by 1901, this number had nearly doubled to 6,371.[18] In the days when the death knell was tolled (1875), “only about a dozen children – mostly infants a few days old – have died in the district [in two months], excepting three deaths at the Union of persons not necessarily belonging to Berkhampstead”. In common with the rest of the country, child mortality was still a problem, driving an increase in the number of offspring, though it is evident from contemporary memoirs that this “never compensated emotionally for those who were lost”.[19] In 1876, Mr. Read reported that the death rate in the town was very low; Mr. Hadden replied that Berkhamsted should be the healthiest place in England, a remark that was met with cheers. In 1878, it was proudly announced that there were upwards of 90 natives of Berkhamsted who were between 80 and 90 years of age “which speaks well for the healthiness of the place”. A decade later, “Four old men were in a barber’s shop… whose united ages amounted to 333. One was 86, the next 85, and the two juveniles 81 years each.”[20] Long life and good health to all in Berkhamsted!

[1] Bucks Herald (Oct 1874)

[2] Hastie, S., Berkhamsted: An Illustrated History (1999), p.69

[3] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (Sep 1865)

[4] Rollitt, L., ‘Red Lion Yard’, The Chronicle, v.XII, p.30

[5] Bucks Herald (Jun 1874)

[6] Bucks Herald (Jul 1875)

[7] Bucks Herald (Jul 1875)

[8] Bucks Herald (Feb 1876)

[9] Bucks Herald (Sep 1876)

[10] Bucks Herald (Nov 1888)

[11] Thompson, I & Bryant, S. Extensive Urban Surveys: Berkhamsted, Revision (2005), p.26

[12] Birtchnell, P., Short History of Berkhamsted (1972), p.64

[13] Bucks Herald (Jul 1877)

[14] Bucks Herald (Oct 1891)

[15] Luton Times and Advertiser (Jul 1904)

[16] Hertford Mercury and Reformer (Aug 1868)

[17] Bucks Herald (Jun 1889)

[18] Schofield, R., Parish Register Aggregate Analyses (1998) & 1901 census

[19] Crone, V., ‘Was Victorian Life Really So Grim?’, HistoryExtra (Nov 2015)

[20] Bucks Herald (Nov 1875, Feb 1876, Mar 1878, Sep 1888)