Challenging the myth that medieval cooks and food-sellers disguised their “poky pigges and stynkynge makerels” with spices, Carole Rawcliffe explains that there were stringent rules and regulations enforced locally, with harsh punishments for offenders.[1] In Berkhamsted, food standards included ensuring fair weights and measures, detection of adulteration or misrepresentation, and enforcing procedures for the sake of public health.

The town’s regulators were appointed during ancient ceremonies at the Court Leet for the Manor of Berkhampstead held at the Court House in Back Lane (now Church Lane). For example, in 1866:

C.E. Grover, Esq., solicitor [steward] for Earl Brownlow, was in attendance. Messrs. J. Redding and G. Brockwell were appointed ale-tasters, Messrs. John and Charles Tompkins flesh-tasters; Messrs. W. Hazell and T. Thomas, water-bailiffs; and Mr. R. Lindsey, scavenger.[2]

It was the duty of the tasters to prevent the sale of unfit or unwholesome ale or meat for human consumption. Water bailiffs monitored rivers and lakes, determining fishing rights, protecting environments and wildlife. Scavengers ensured standards of hygiene in the “lanes and privies” of the town to guard against the spread of infectious diseases; often churchwardens and overseers of the poor, they might employ paupers to sweep the streets.[3] Many Court Leets survive to this day, possibly drawn by the prospect of ale-tasting!

When the parish constables of Berkhamsted took on their year’s duties, as well as keys and hand-cuffs, there was a ceremonial handing over of a set of brass weights and scales so they could inspect local tradesmen and ensure that they were not selling underweight provisions.[4]

In 1839, Augustus Smith presided over Petty Sessions in Berkhamsted where several of the town’s vendors were sentenced for deficiency in weights and measures: grocers John Allum and Richard Harris; butcher John King; David Duncombe (unspecified). Also three traders of Northchurch: James Osborne, James Lawrence and beer house keeper James Eames. Fines ranged from two to 13 shillings and all paid eight shillings in costs. Duncombe paid the most at nearly £50 in today’s money.

Despite regular scrutiny, prosecution and fines being levied, which must have damaged reputations, nothing much had changed by 1873 when Inspector Goodyear prosecuted several local shopkeepers for using light weights: bakers George Harbourn, Charles Clarke and Charles Kingham; grocers Henry Norris, Francis Clay, John Pearce, Thomas Mead, Henry Newell and one grocer/butcher William James; fishmonger James Griffin and marine store dealer James Coughtrey.[5]

Watering down products seems to have been a favoured method for tradesmen to cheat customers in Berkhamsted. In 1905, James Brown, who had been the landlord of the Crown for 27 years, was charged with adulterating whiskey. The inspector of weights and measures, Mr. W.G. Rushworth, showed that a sample of whiskey contained 30 per cent water, whereas only 25 per cent under proof was allowed.

Defendant said he bought spirits at proof strength and broke them down to 22 under proof. When he had tested the mixture he had always found it correct : he did not test that particular mixture, as he was too busy. The Bench convicted, the Chairman remarking that it was due no doubt to carelessness, but there should be no carelessness in such matters. Defendant was fined £1 and 19s. costs.[6]

In the same year, a case of milk adulterated with six per cent water was heard at Great Berkhampstead Petty Sessions. The perpetrator, Rayner P. Wray, also charged with obstructing the efficient Inspector Rushworth in the performance of his duty, offered a rather implausible excuse and was fined £6 9s.:

The evidence showed that defendant upset the can containing the [milk] when asked by the Inspector for a sample, though the officer succeeded in saving about half of it. The defence was that it was not milk, but water used for rinsing milk cans, and that some milk had been poured into it in mistake.[7]

Towards the end of World War One, a butcher named Edwin Young was fined £20 with four guineas costs for illegal sales of horse flesh:

Defendant admitted killing his pony with the intention of boiling it for pigs: but, as he had no meat for sale, and kept turning customers away, he cut out the best part and sold about 30 pounds. He denied saying it was beef.[8]

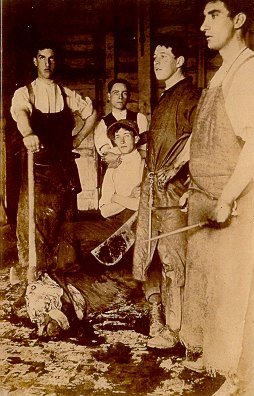

Members of the Tompkins family were often appointed flesh-tasters at the Court Leet. Their butchers’ shop was opposite the Crown and their slaughter house was behind the shop in Back Lane.[9] This photo depicts a day in the life of the Tompkins family: men leaning on their axes over the carcass of a sheep in a pool of blood.

Magistrates imposed penalties on any who did not follow practical rules for public health:

It was illegal to kill animals in the market; if meat was kept after 12

hours, it had to be salted; chopping boards couldn’t be used for 2 days running; carts carrying food stuffs had to be covered because of miasma; they had sell by dates; pork couldn’t be sold in the summer…[10]

The miasma theory of disease was later replaced by the germ theory but it was still prevalent in the 1870s, when an alternative solution to an expensive sewerage farm (estimated at £30,000) was proposed for drainage problems in the town (more about this in the article Health Hazards in Victorian Berkhamsted):

It is absolutely necessary to adopt some method of disposing of the sewage of the town of Great Berkhamstead in some other way than… discharging the greater portion of it into the river. It has been thoroughly proved… that all close drains should be constantly flushed and ventilated, for if these precautions are not taken they will generate that most poisonous gas called sewer miasma… insidious breeder of the most dangerous fevers.[11]

The Bucks Sanitary Conference of 1894 was attended by R. Bailey on behalf of Berkhamsted.[12] During their discussions about public health and the purity of the food supply, the question of competition from abroad was raised, particularly the rapid growth of the butter trade in Denmark. This was attributed to their Government’s insistence on “the minute and continuous care in the matter of cleanliness, resulting in the production of milk and butter of the very finest quality”. The meeting agreed that “the produce of England should be as good as that which came from any other part of the world”. None other than Florence Nightingale sent a letter wishing the chairman Mr Verney “God’s speed”:

These conferences will be of immense use. Health is really of so much more consequence than disease, though we have only lately found this out. Good speed to the medical-officers of health and all the ‘pursanianto’ of health, lay and professional.

A worthy aim arising from the meeting was “to prevent disease where it could be prevented, to save life where it could be saved, and to get rid of evils arising from neglect, filth, and other conditions which contaminated the air and the water”.

[1] Rawcliffe, C., Poky pigges and stynkynge makerels: Food standards and urban health in medieval England (Feb 2015)

[2] Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette (Nov 1866)

[3] ‘Scavenger, n.’, OED Online (Dec 2016)

[4] BLH&MS, Constables Book of Accompts (1748-1819)

[5] Bucks Herald (Nov 1873)

[6] Bucks Herald (Sep 1905)

[7] Bucks Herald (Oct 1905)

[8] Western Daily Press (Feb 1918)

[9] Hertfordshire Archives & Local Studies (HALS), Berkhamsted Tithe Map and Apportionment, HALS DSA4 19/1 & 2 (1839)

[10] Rawcliffe, Poky pigges

[11] Herts Advertiser (Apr 1876)

[12] Bucks Herald (Oct 1896)