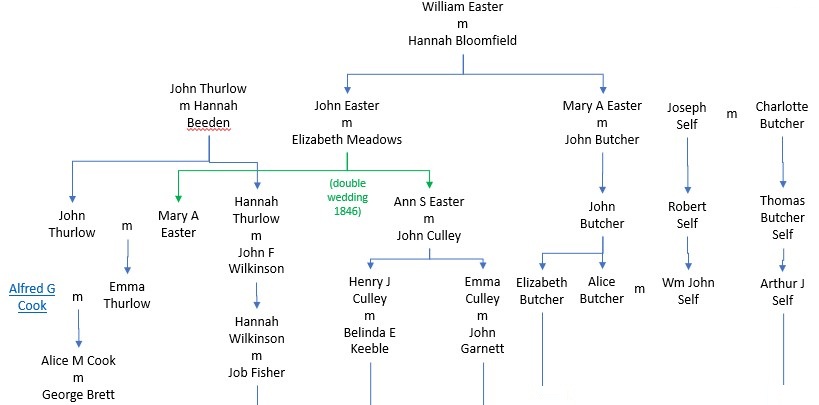

Mary Ann Easter was born in 1825 in Great Glemham Suffolk. On 1 Oct 1846 in Aldeburgh, she married John Thurlow of Butley in a double wedding with her sister Ann Sarah Easter and John Culley, witnessed by siblings John and Emma Easter.

The Easters’ parents were John and Elizabeth (Betsey) née Meadows. John was a farmer at Brick Kiln Farm in Aldeburgh between 1841 and 1851 and was still farming in Hazlewood when he died in 1865 of valvular disease of the heart which he had suffered for four years. His son Henry Thomas Easter was present at his death.

John Easter was baptised on 10 Jan 1800 in St Peter and St Paul church in Aldeburgh to parents William and Hannah née Bloomfield. John’s sister Mary Ann Easter was born in 1811. She married John Butcher of Orford and their granddaughter Alice married into the Self family.

Some Aldeburgh-based DNA matches are descended from the Self and Butcher families. Being fishermen, these families had their share of tragedies. Thomas Butcher Self (1838-1892) and his brother Robert Francis Self (Alice’s father-in-law) were lost at sea after a collision of smack Alfred Louisa with Dundee clipper Airlie…

All hopes are now given up of the return of the Aldeburgh smack Alfred Louisa which left Aldeburgh Bay a short time since to complete the season’s fishing off the Smith’s Knowl Sands, to the north of Great Yarmouth. The smack had a crew of eight hands, including the skipper, Mr. Robert Self, who was greatly respected, not only by his townsmen, but all of the people of the different ports of the East Coast. He was considered one of the most able and skilful skippers afloat. There is little doubt that the smack sank after collision with the Dundee clipper Airlie. The Board of Trade are making strenuous endeavours to trace the crew of the clipper, who were paid off directly on arrival at Dundee. In a letter in answer to a telegram, as regards the fate of the crew, the captain writes:- “The night was clear, but very dark – good for seeing lights, but bad for seeing ships. We hard ported our helm to a vessel ahead, and about three minutes afterwards we saw a vessel within two ships’ lengths of us, who suddenly showed a red light. There was a lumpy sea on and a fresh breeze blowing, and before we could clear her, her masts caught our jib boom, and then, I suppose, we must have run over her. They must have seen us approaching long enough to have had time to put their boat out, but whether they did or not I cannot say. I wore our ship round at once, and got her on the other tack until we got amongst some floating wreckage, broken spars, and one or two life-buoys, which we had thrown them when we had struck her, and then hove to, and remained so till 4.15 a.m., till it was good daylight, and then, before we kept on our course again, I sent hands aloft to the topsail yards to have a good look round, but they could not see anything”.

(Yarmouth Mercury, 11 Jun 1892).