Economic, humanitarian and religious arguments were part of the abolitionist’s armoury in their fight against the lucrative slave trade at a time when slavery was lawful, even normal, in British society.[1]

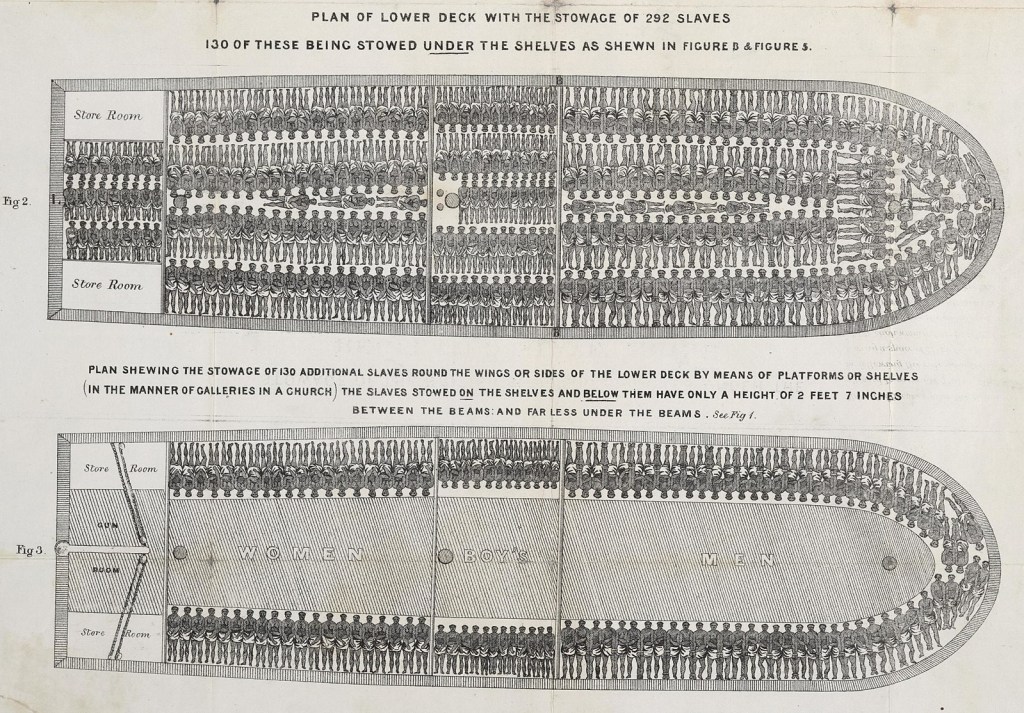

For many years, abolitionists lacked effective arguments against planters’ assertions that the slave trade was essential for Britain’s wealth.[2] William Wilberforce MP outlined a stark economic reality to Parliament: the high level of mortality among seamen and slaves (who were not bought unless quite healthy) during sea voyages.[3] Thomas Clarkson shocked the public with a poster demonstrating one of the causes of so many deaths (between five and 20 per cent) – the appallingly cramped conditions on board Liverpool ship “Brookes”.

Advocates of slavery believed they were saving Africans from an uneducated, savage existence, but art, learning and technology flourished there before European slavery.[4] Clarkson presented examples of African skills and craftsmanship on his travels around the country to “demonstrate that Britain could trade profitably with Africa in something other than human beings”.[5] Africans suffered grievously from being removed from their homeland, as demonstrated by their melancholy songs and attempted suicides.[6]

In Hertfordshire in 1830, petitions for the abolition of slavery were signed by John Eales, surgeon Richard Steel and Quaker Thomas Squire of Berkhamsted, James Smith of Ashlyns, Astley Paston Cooper of White Hill and miller William Littleboy of Northchurch:

To the High Sheriff of the County of Herts.

We, the undersigned Freeholders of the County of Hertford, request you to call a meeting of the Freeholders & Inhabitants of the County, to consider the propriety of petitioning Parliament to take measures, with a view to the early abolition of slavery, throughout the Colonies of the British Empire.

A well-known son of Berkhamsted, William Cowper, was asked by William Wilberforce to write poems which would help bring the slaves’ plight into the public domain:

Men from England bought and sold me,

Paid my price in paltry gold;

But, though slave they have enrolled me,

Minds are never to be sold.

This was at a time when slave ownership was lawful, with prominent politicians influencing events and furthering their own interests. Charles Darling was a Conservative critic of William Ewart Gladstone, attacking him via newspaper letter pages for lack of compassion due to his ownership of slaves and had been rebutted with a letter that his claims were “an absolute falsification of facts.” [7] Darling responded: “We knew how Mr. Gladstone had made his money. He was like Mr. Chamberlain – ‘who toil not, neither do they spin.’ Mr. Gladstone made his money out of slaves”. He went on to detail Gladstone’s father’s sugar plantation at Vreeden’s Hoop in Demerara where 553 slaves toiled for his advantage and through “over-exaction of labour” that number had been reduced by death to 472. In Parliament, Gladstone professed a belief that slavery was “abhorrent to the nature of Englishmen” and “an evil and demoralising state”, but in filial loyalty he had also defended his father’s estate, saying that only “old Africans” had died.[8]

Charles Gordon (1747-1829) was a descendant of Elizabeth Gordon of Braco, wife of William Gordon of Avochie in Aberdeenshire. Accounts filed by overseer Robert Gibb show that the Braco Estate in the Trelawny parish in Jamaica was owned by Gordons Bank of Pimento Walk in St Ann’s Jamaica from 1790 to 1795.[9] The estate produced sugar, rum and pimento. By the end of the century, under the ownership of Charles Gordon Esq., the estate had diversified into cattle, horses and coffee. James Robertson’s 1804 map of Jamaica plotted Trelawny as a sugar estate with two cattle mills. From 1815, the accounts start to record the number of slaves on the estate. The fall in numbers in 1826 was due to 60 slaves being transferred to Richmond Pen, St Ann’s, another estate owned by Gordon:

How is this relevant to Berkhamsted? As tangible proof of the huge profits made from what powerful West India lobbyists at the time depicted as a respectable trade, Charles Gordon owned property in Gower Street London and Pilkington Manor in Berkhamsted, situated between Castle Street and Ravens Lane. The Manor included house, yard, stables, pleasure ground, garden, orchard and meadows.[10] Also included were the land either side of the canal to the west of Gravel Path and the meadow and wheeler’s shop east of Holliday Street.[11] In 1832 his son Charles (1784-1839) bought Newtimber Place, Sussex, still held by the family.[12]

Mrs Mary Gordon lived at Pilkington Manor. She made so many claims against “The Great Berkhamsted and Northchurch Association for the security of persons and property of the subscribers”, founded in 1794 (forerunner to Neighbourhood Watch) that she was asked to withdraw from the association. She could well have afforded to meet any losses she suffered, simply by dipping into the considerable family wealth.[13]

A small glimpse of grandeur behind the high walls of Pilkington Manor is afforded when a crime was committed there in 1824. Charles Cartwright and William Marshall were indicted for breaking and entering Charles Gordon’s house and stealing various articles of gold and silver plate, along with bank notes and gold coin to a large amount (equivalent to £6,260 today). Marshall had knowledge of the household as he was formerly an upper servant in Mr. Gordon’s family. Next morning, a servant discovered the burglary. He missed several items from the pantry, his master’s writing desk was on the lawn, papers scattered, clothing strewn in the hedge between garden and meadow and a cucumber-frame and net were thrown into the fishpond.[14] A few days later, both prisoners were executed in front of Hertford gaol.[15]

The Anti-Slavery Society had mobilised public support; deputies from all over the country were sent to London in a final push that secured an Act abolishing slavery in 1833. By this time, slave-owning was doomed. Difficult final negotiations involved appeasing the planters by proposing a “system of apprenticeship (slavery under another name) and that compensation should be paid to planters for loss of their ‘property’”.[16] With the French Revolution still fresh in mind, the state was careful not to ride roughshod over property rights.

Backing for compensation inevitably came from Gladstone. Whilst deprecating cruelty and slavery “abhorrent in the nature of Englishmen; but conceding all things, were not Englishmen to retain a right to their own honestly and legally acquired property… He trusted that the House would make a point to adopt the principle of compensation”.[17] The House duly voted to compensate planters using twenty millions of public money. Gladstone’s father was paid £1:18:4 per slave, half above the average. Charles Darling cynically pointed out that “This difference is probably explained by your having proved that the ‘old Africans’ had been eliminated – wherefore the robust residue commanded a higher price”.[18]

As part of this government’s compensation scheme, “Charles Gordon, residing in England, got £4476 4s 11d compensation for 221 slaves on the Braco estate Trelawny; £1171 for 98 slaves on the Williamsfield Pen, Trelawney, Oct.19, 1835; and £1931 7s 4d for 84 slaves in Richmond Pen, St Anne’s, Feb. 1, 1836”.[19]

Charles Gordon’s death was announced in the Gentleman’s Magazine: “Jun 25 [1829]. Aged 83, Charles Gordon, esq. of Great Berkhamsted, and of Braco, in Jamaica.”[20] An inscription in the Lady Chapel of St Peter’s church reads:

In memory of Charles Gordon Esquire of Braco the island of Jamaica and of this place who departed this life on the 25th of June 1829 aged 82 years. His remains are deposited in the vault of Pilkington manor House. Also of Eliza Anne Gordon third daughter of Charles Gordon Esq who departed this life 16th April 1820 aged 25 years. Also of Mary wife of the above Charles Gordon who died 18th June 1839 aged 75 years.

In Charles Gordon’s will, he explained that he left no pecuniary bequest to his son Charles having already advanced him sums “on account of the New Timber estate”. He left Braco in trust for Charles Gordon and bequeathed the principal of the £34,228 8s 3d consolidated annuities (worth nearly £3.5 million today) in trust for his three sons and their heirs after the death of his wife. The Gordon family had indeed prospered from the slave trade.

Slavery was finally abolished in Aug 1834. Religious and moral arguments against slavery, along with humanitarian feeling, brought about social changes. British tax-payers had effectively subsidised West Indian planters but now the slave system was “not so much rendered unprofitable, but by-passed by the changing economic and social order in Britain”.[21]

[1] Rollitt, L., Abolition of slavery (2016) (unpublished); British Empire course at Oxford University used as basis for investigation of slave owner in Berkhamsted

[2] Porter, A., ‘Trusteeship, Anti-Slavery, and Humanitarianism’, Oxford History of the British Empire, Volume III (1999), p.8

[3] BBC, Abolition of British Slavery http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/abolition/ (accessed Oct 2019)

[4] International Slavery Museum, ‘Africa before European slavery’, The history of the transatlantic slave trade

[5] BBC, ‘The unsung heroes of abolition: Thomas Clarkson’, Abolition of British Slavery

[6] Falconbridge, A., An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa (1788), p.23,30-32

[7] Bucks Herald (Feb 1884)

[8] UK Parliament, Hansard’s Debates (14 May & 3 Jun 1833)

[9] University College London (UCL), Legacies of British Slave-ownership database (2019), https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/2065 (2019)

[10] Sherwood, J., ‘Pilkington Manor, another lost house in the High Street’, Your Berkhamsted (Oct 2015) p.11-12 records the history of the Manor

[11] HALS, Berkhamsted Tithe Map, DSA4/19/2 (1839); land owned by the Executors of Charles Gordon Esquire [Jr]

[12] Bulloch, J.M., The Making of the West Indies: The Gordons as Colonists (1915), p.24

[13] Cook, J., Berkhamsted Review (Nov 2000)

[14] Morning Chronicle (31 Jul 1824)

[15] Newcastle Courant (21 Aug 1824)

[16] Hall, C., ‘Anti-Slavery Society (act. 1823–1833)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Jan 2016)

[17] Hansard, Vol. XVIII, p.330

[18] Bucks Herald (Feb 1884)

[19] Bulloch, Gordons as Colonists, p.24

[20] Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol 99, Part 1; Vol 145 (1829)

[21] Oldfield, J., Popular Politics and British Anti-Slavery (1995)